Frida Kahlo (2020)

Kristin here:

I wonder how many of my readers will recognize the source of this entry’s title. Is Monty Python’s Flying Circus still the perennial classic it was among young people for decades after its original series was broadcast? That brief sentence was the title of the sixth episode of the first season, shown in 1969, though I didn’t see it until some years later. The episode itself has little to do with the arts, but for some reason that particular title stuck with David and me, as few if any others did. Whenever we have encountered a TV program or a review, often something pretentious, one of us will turn to the other, or both simultaneously, and say, “It’s the Arts!”

The Vancouver International Film Festival has an admirable custom of showing many documentaries. They often deal with ecological issues and Canadian subject matter. One prominent thread, however, is documentaries about the arts. These are known as MAD, or “Music, Art and Design.” Although, as I mentioned in my previous entry, I tend to stick to the Panorama program of international fiction films, I always try to attend a few of these arts documentaries when they fit in with my interests. Most of these are in fact wonderful, not pretentious. Still, I am too accustomed to the phrase, and I think automatically, “It’s the Arts.”

Paris Calligrammes (2019)

One documentary that I was keen to see is Ulrike Ottinger’s autobiographical account of her years living in Paris during the 1960s. Ottinger is known, at least in the US, primarily for her experimental fiction films, like Freak Orlando (1981) and Joan of Arc of Mongolia (1989). I had not encountered her work since then and was eager to catch up with her at this year’s festival.

Ottinger did what many young people think of doing but never carry through on. She left home at the tender age of twenty for an exciting new life. In 1962, she moved from Germany to Paris, where she lived until 1969 before returning to West Germany. In France she lived among Bohemians and stayed long enough to witness the protests of May, 1968.

Naturally she was hugely influenced by her experiences. She tells of encountering artists and ideas: “In my euphoria, I wanted to convert all my experiences directly into art.” But how? Early on, she muses on how to convey those experiences of decades ago:

I ask myself that same question over fifty years later. How can I make a film from the perspective of a very young artist I remember, with the experience of the older artist I am today? In Paris, I followed in the footsteps of my heroines and heroes. Wherever I found them, they will appear in this film.

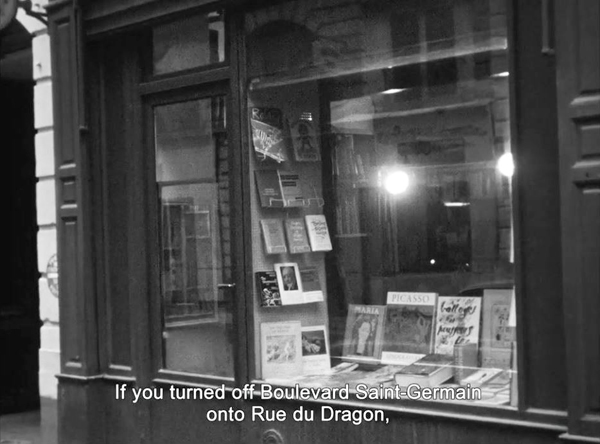

There is no footage of Ottinger from this period, and relatively few relevant photographs. Instead she wisely organizes the early portions of the film around her connection to an extraordinary bookshop that was a center of artistic and intellectual life at the time: Calligrammes (above), founded in 1951 by Fritz Picard, who had fled Nazi Germany in 1938. As a dealer in rare German and other books on the arts, Picard became host to innumerable avant-garde artists and intellectuals. Ottinger recalls buying many books on the German Expressionists and other avant-garde artists and movements of earlier decades.

(David bought some books for his dissertation on French Impressionist cinema at Calligrammes in the summer of 1973. Picard died in November of that year, though the shop was continued for a time by others.)

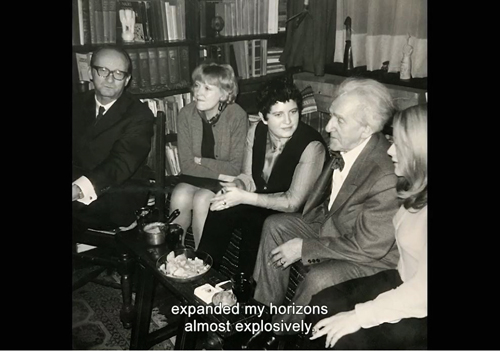

Ottinger became a friend of Picard and socialized with the patrons and visitors of the shop. Below, she’s in the black vest, sitting beside Picard at a party. She also was indirectly influenced by the great artists of the past, such as Hans Richter, who had frequented Calligrammes. In one sequence she flips through the guest-book signed by many a famous visitor, and we see clips from films like Ghosts before Breakfast, which influenced her.

Following this section, Ottinger gives us sequences on the effects of the Algierian war on her friends in Paris and describes the protests of May, 1968, some of which she was able to see from her apartment near the Sorbonne.

Perhaps inevitably, Paris Calligrammes reminded me of some of the Agnès Varda’s late autobiographical work. Ottinger is less lyrical and personal, as well as being more overtly political. There is more of a sense of name-dropping, at least in the early section. Still, who wouldn’t be interested in hearing about the early life of someone who has had such adventures? Ottinger also describes the influences on her by the artists she learned about and met. The brief clips from her own films should inspire a new generation of film buffs to seek out her work.

Like so many of the films at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year, Paris Calligrammes was shown in Berlin. For an enthusiastic and informative review done at the time, see Richard Brody’s piece in The New Yorker.

Marcel Duchamp: The Art of the Possible (2020)

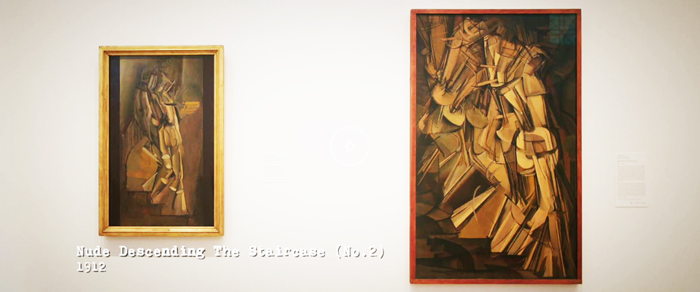

I am of two minds about Matthew Taylor’s documentary on Duchamp. It presents an excellent overview of the artist’s career and work, and one could learn a great deal from it. It makes clear, for example, the relationship between Duchamp’s early ready-mades and the fact that they were mostly subsequently lost and much later replaced by replicas–all with the artist’s cooperation. It puts his important early painting “Nude Descending a Staircase” (see bottom) in its historical context.

There are the usual experts explaining Duchamp’s intellectual approach to his artworks and his considerable influence on subsequent generations. We are not given much indication concerning who some of these experts are. The identifying labels often just say “Curator” or “Art historian” without linking the experts to any institution or publication. I tried looking one of them up on the internet and couldn’t find him. I’m sure, however, that they know Duchamp’s life and work well.

These experts are also almost all extremely enthusiastic about Duchamp’s work and especially the impact he has had upon art–not, as they emphasize, just specific trends but absolutely all subsequent art up to the present. Early on in the film, before we have been introduced to most of the talking heads, a voiceover declares, “Without him, imagine where we would be. We’d be painting in the style of Matisse or Picasso. That’s what modern art would be without Duchamp.”

(Ironic note: Duchamp’s stepson, Paul Matisse, is the grandson of Henri Matisse.)

That’s a pretty remarkable claim. It’s hard to think of a period that long in the post-Medieval era when art has just frozen in place for a century. Surely innovative styles and individual artists would have come along and produced distinctive work that did not depend on Duchamp’s main claim to fame, his demonstration that anything could become an artwork if we regard it as such. Did the Soviet Constructivists depend on Duchamp’s idea? Did the German Expressionists? Do highly individualistic artists? (See the section below.) Do manga and graphic novels, which are coming to be thought of as worthy of attention as art–not just because someone found them and declared them so, but because they contains qualities that were considered artistic well before Duchamp?

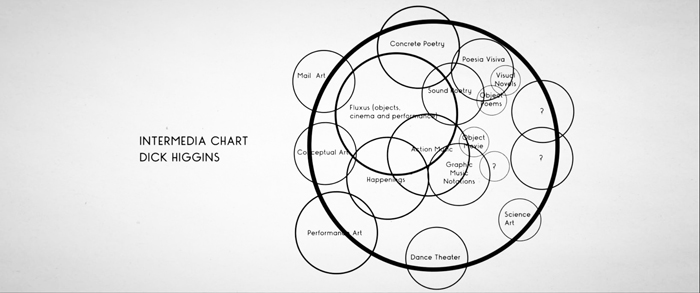

To be sure, Duchamp did have a huge impact, as this chart, shown in the film, suggests. It was devised by Dick Higgins, artist and co-founder of Fluxus. (The absence of Pop Art among the circles is rather puzzling, though it does figure in the film.) One could, however, devise many other circles for trends and institutions that do not reflect that impact.

Toward the end of the film, the experts go further, suggesting that Duchamp encourages the democratization of art by suggesting that anyone can be an artist, whether on their own or by taking and re-purposing existing artworks or objects or sounds. Yet would we say that the many outsider artists of the past century who have come to the recent attention of taste-makers had anything to do with Duchamp? And fanart, if that is included in this vast generalization, existed before Duchamp.

Despite the obvious excitement the experts display in extolling Duchamp’s work, someone watching the film might be less sympathetic, given the debatable state into which Postmodernism in general has led the art world. As one inevitably thinks, what’s next, Post-Postmodernism?

Duchamp himself seems, according to the film, to have had considerably less enthusiasm about his own artworks, preferring perhaps the idea of them rather than the execution. He took twelve years to complete the Great Glass and declared himself pleased with the results when an accident severely cracked its surface. He did not bother to keep track of his ready-mades, most of which disappeared. One wonders why he bothered to follow the initial venture into that area with “Fountain” (a urinal signed “R. Mutt 1911”), since subsequent ready-mades like “Hat Rack” (above) make the same intellectual point.

Late in life Duchamp seemingly gave up art-making to devote himself to competitive chess. After his death it turned out that from 1946 to 1966 he had been working on “Étant donnés,” a peep-show view of a spreadeagled nude woman, based on his mistress during part of that time. Despite the raptures expressed by the experts, it looks like it could be considered revenge porn. But only, presumably, if one calls it that.

Only one of the experts, Peter Goulds, departs from the general unquestioning idolization of Duchamp. Near the end he says,

Later in life, of course, he must have found it incredibly amusing to hear people latch onto his theories as though they were universal truths, when actually his whole life was about bucking those very conventions and defying them. So I’d like to suggest that his form of so-called conceptual art was a much more playful exchange. I’m not so sure about how even serious he was about it himself. Here he throws these things out as suggestions, with thought. Others, perhaps more needy than himself, would make these rules be therefore solely applicable.

Frida Kahlo (2020)

Frida Kahlo is one of those artists who don’t appear to owe much, if anything to the influence of Marcel Duchamp. As the film makes clear from the start, she was aware of European artistic movements and developments. Still, neither she nor her husband, muralist Diego Rivera, seem to have absorbed much from them. Kahlo always denied that her later work was Surrealistic, and one might rather attribute its fantastical elements derive more from the Latin American tradition of Magical Realism.

Indeed, the whole idea that Duchamp influenced all of modern art comes to seem remarkably Amero- and Euro-centric if one considers that it implicitly either scoops highly individual artists like Kahlo up into one enormous category or eliminates them from that category altogether.

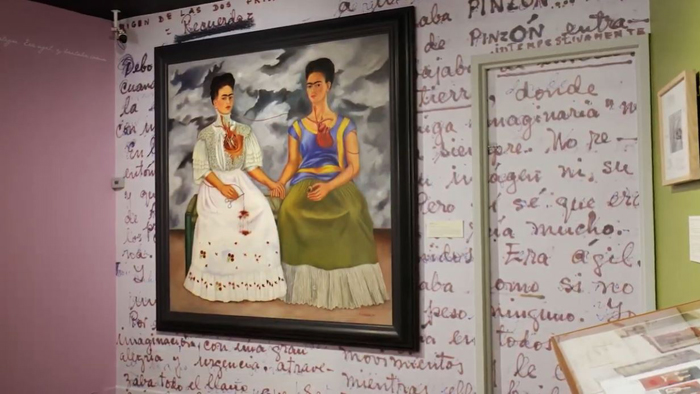

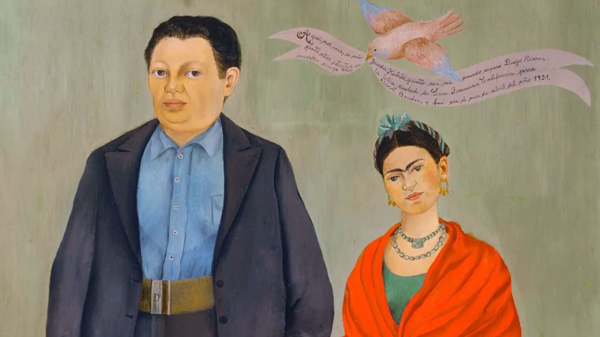

I found Frida Kahlo more satisfying than Marcel Duchamp. Its experts are all clearly identified as to their position and institution. Some are curators of the institutions which own her works, such as the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City. There “The Two Fridas” is shown (see top) as the curator discusses it.

These experts are as enthusiastic about their subject as those in the Duchamp film, but they are focused entirely on recounting Kahlo’s life, her social context, and the influences on and changes in her style across her life. For example the simple presentation of “Frida and Diego Rivera,” an early portrait done shortly after their marriage, gives way to the more sophisticated and symbolic “The Two Fridas.”

Archival photographs and film clips illustrate the eras of the places where Kahlo lived and traveled. The impact of the lingering effects of her injuries in an extremely serious traffic accident in her youth, her travels with Rivera in the US, and the rockiness of their marriage are all discussed to help clarify the often cryptic visual references in her paintings.

In short, Frida Kahlo is a model of a staightforward and informative documentary on an artist. I was pleased to be introduced by it to its producers, Exhibition on Screen. In business since 2011, it has made twenty-six such documentaries. These are shown in theaters and festivals initially, before being made available on disc and streaming on their website. Frida Kahlo is promised for streaming on October 20.

Once again, thanks, as usual to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, Curtis Woloschuk, and their colleagues for their help during the festival.

Marcel Duchamp: The Art of the Possible (2020)

from Observations on film art https://ift.tt/3neU31Z

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento