“Frame-Up for Murder” (“Murder Is No Joke”), Saturday Evening Post (21 June 1958).

DB here:

“It is impossible,to say which is the more interesting and admirable of the two.” Thus Jacques Barzun on Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin, the characters created by Rex Stout. I’d go farther. For me they are among the outstanding figures of American fiction, and Stout is one of the finest American writers of the twentieth century.

Wolfe and Archie are detectives, and Stout wrote mystery fiction. But that just goes to prove that genre work isn’t just good “of its kind.” It’s often good, period.

Stout started as a pulp novelist. He moved to what we now call literary fiction before pursuing a variety of more mainstream genres. He wrote quasi-experimental novels (one is told backward), comic romances, lost-world sagas, and a political thriller, The President Vanishes. (Stout admitted that Wellman’s film version was better than the book.) He introduced several other detective protagonists, but he wisely concentrated on Wolfe and Archie, whom he launched in 1934 and traced through dozens of adventures until his death in 1975.

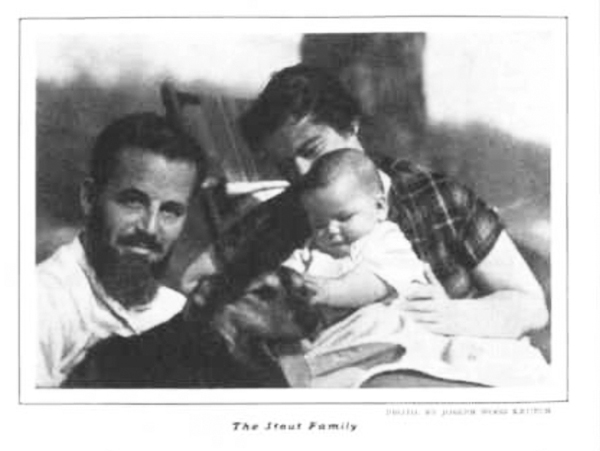

Here is Stout with his wife Pola and daughter Barbara in 1935.

Are these stories still read? I hope so. When I quizzed the grad students in my seminar this spring, most seemed unaware of what for me–and, I think, other baby boomers–were major figures in popular culture. It’s partly because the ancillary media never did a good job spreading the word. The film Meet Nero Wolfe (1936) was weak, in keeping with the general failure of 1930s films to capture the strengths of supersleuths like Philo Vance and Ellery Queen. (Better were the Mr. Moto and Charlie Chan vehicles.) During the late 1990s, Bantam reprinted the books in quality paperback editions, with introductions by other writers (Westlake, Lippman et al.). There was a solid cable-TV series (A Nero Wolfe Mystery) back in the early 2000s, with a trying-a-bit-too-hard Timothy Hutton as Archie but a near-definitive Wolfe in the form of Maury Chaikin. But that’s all pretty far back now.

O well . . . . If Perry Mason can come back, maybe Wolfe and Archie can too. And they won’t be scruffy and unshaven. Archie explains: “I was born neat.” So was his prose.

Today, I’m posting a long (22,000 words!) essay on Wolfe and Archie in an effort to show some reasons they and their creator matter. Background follows below.

Research? Say rather, obsession

Like most academics, I try to pour my obsessions into my research. My interest in mystery stories (fiction, film, even theatre and TV) is surfacing in my current project, a book studying principles of popular narrative as they emerge in thrillers and detective stories. In a way, the book turns inside out what I tried to do in Reinventing Hollywood. There I traced film techniques to sources in adjacent media. Now I’m looking directly at those media to consider their formal and stylistic strategies, with some consideration of how film shaped and was shaped by them.

My survey covers familiar ground. I consider the classic detective story (the so-called “Golden Age” of Christie, Sayers, Queen, Carr et al.), the hardboiled writers, the suspense thriller, and the crystallization of major techniques in the 1940s (a polemical point with me). Later chapters analyze the heist plot, the police procedural, and particular writers (e.g., Cornell Woolrich, Ed McBain, Richard Stark, Patricia Highsmith). As presently planned, the book ends with an odd-couple pair of chapters: the “puzzle film” trend of the 1990s, and the domestic thriller of recent years (Gone Girl, The Girl on the Train). Some chips from the workbench have littered this blog, as the links indicate.

One of my key questions is: What has enabled readers and viewers to welcome the sort of extreme complexity that we find in movies like Pulp Fiction or Memento? We’re all now connoisseurs of narrative intricacy, in not only crime plots but science-fiction and fantasy ones (which actually often rest on mysery premises; see Devs).

And traditional genres. I’ll argue that modernist experiments provided some strategies that mystery writers could recast within the bounds of their tradition. Stout’s first two serious novels, How Like a God (1929) and Seed on the Wind (1930) joined the trend toward mainstreaming modernism. By 1930 he had fully absorbed what the 1910s-1920s writers had achieved. What’s less obvious is the mark of modernist writing on his reader-friendly detective stories. Yet one lesson of modernism, I think, is the need to play with language, to “defamiliarize” literary texture. That, I think, is one of the tasks Stout took on in the Wolfe saga.

I had planned to include a chapter on the Wolfe/Archie series, but what resulted was far too long in comparison with its mates. So I’m posting it online as an essay. A shorter version will show up, somehow, in the finished book.

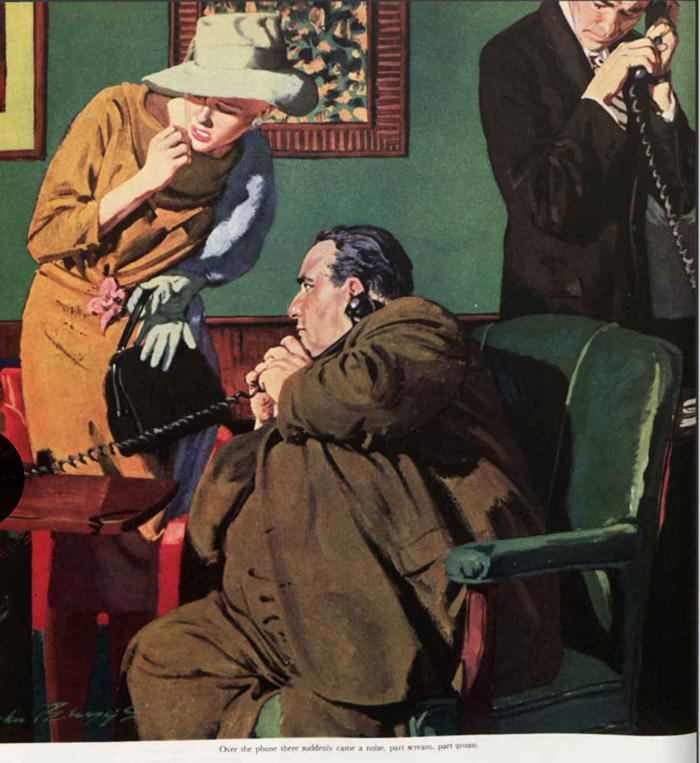

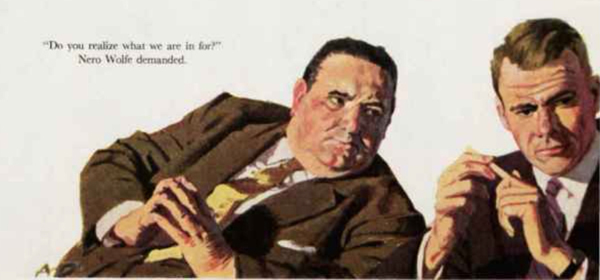

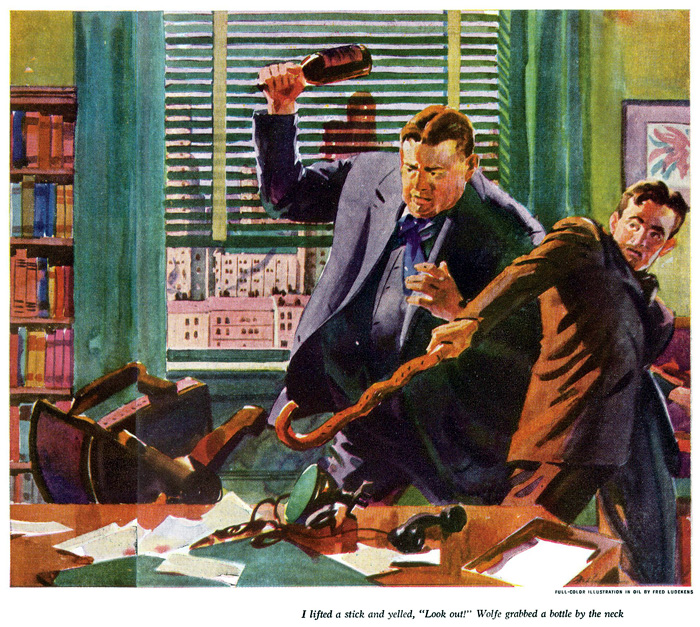

Luckily, thanks to the Internetz, the essay’s web incarnation can include some illustrations from magazine publication of the stories. Since most of the books’ drama takes place in Wolfe’s office, artists are challenged to find nifty ways to show people grouped around a desk.

I hope, then, that fans of the series will find some ideas and information of interest. Above all, I hope what I’ve said here and there will stimulate novices to venture on one of the great exercises in American popular storytelling. If you don’t care for it, all I have to say is: Pfui.

There are many good websites devoted to mystery fiction. The most comprehensive is Mike Grost’s. You should also look into Martin Edwards’ fine blog Do You Write Under Your Own Name? See also the official Wolfe Pack site, full of links and assorted Stoutiana. John McAleer’s biography Rex Stout (Little, Brown, 1977) is vastly informative. Stout was not only a great writer but also a fascinating man.

Fer-de-Lance, serialized as “Point of Death” in American Magazine (November 1934).

from Observations on film art https://ift.tt/3eKHMOm

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento