DB here:

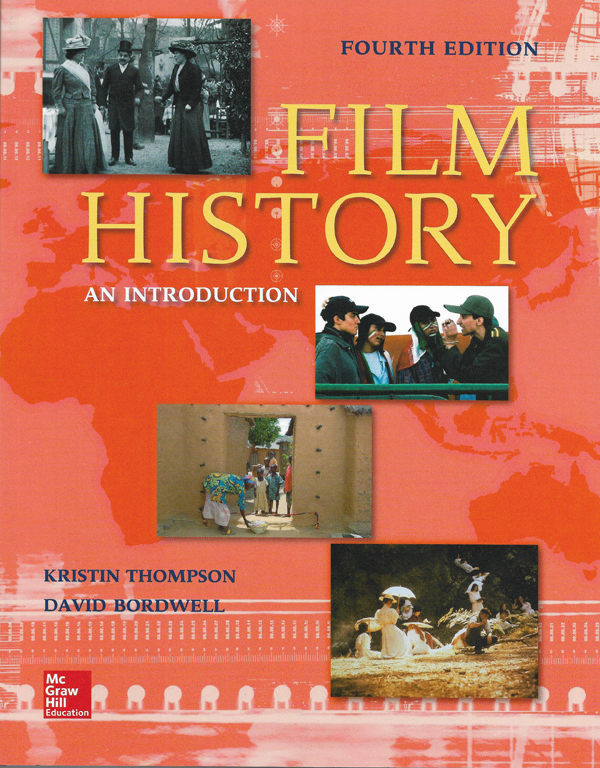

After nine years, here comes another Thompson/Bordwell boulder: Film History: An Introduction in a fourth edition.

When I was in college (1965-1969) my university offered no courses in film. The year after I graduated, my college offered two courses appeared: one, a survey history, the other a study of adaptations. Those pretty much defined the early zones of film studies on most campuses.

In the 1970s, however, the survey history was supplemented by a survey of film aesthetics (sometimes called “film language”), which organized the course not chronologically but conceptually. Weekly topics took up categories like “editing” and “acting,” and usually something about adaptation. Eventually the aesthetic survey became more popular than the historical overviews, and often it served as the introductory course for a major. (Film majors were starting then too.)

It’s likely that our textbook Film Art: An Introduction (1979) contributed to the rise in aesthetic surveys. For reasons rehearsed here, we tried to make it more comprehensive and in-depth than earlier books of that type. We tried to synthesize the ideas developed by film researchers about narrative, filmic modes (documentary, animation), authorship, genre, and film as a vehicle of ideology. We also floated ideas about form and style we developed in our research. Film Art‘s approach proved influential; many later books adopted our conceptual layouts, our terms, and our explications of techniques.

We also tried something that wasn’t common in other “film-language” texts. We included a chapter surveying film history. It was short and very selective, of course, but we tried to show that the expressive resources we surveyed conceptually could also be understood as part of a larger historical dynamic.

About a dozen years after the first edition of Film Art, we published our own version of a synoptic film history. Again, we tried to incorporate film research as we understood it, and—

But wait. I already wrote this, back in 2009. To save you a click, let me quote myself, with some light modifications.

The 1970s: More than disco

Star Wars Uncut: Director’s Cut (Casey Pugh et al., 2010).

For a long time, and sometimes still, film histories written by Americans took a very partial look at the phenomenon of cinema. For one thing, they tended to focus on a series of masterpieces, films that had been deemed important within a narrow canon. The earliest lineup went pretty much this way: Lumière films, Méliès’ Trip to the Moon, Porter’s Great Train Robbery, Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation and/ or Intolerance. Then came national schools, such as German Expressionism (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari), Soviet Montage (Battleship Potemkin), and Continental Dada and Surrealism (Entr’acte, The Andalusian Dog). Early sound was M and Sous les toits de Paris and maybe Love Me Tonight. The 1940s was Grapes of Wrath and Citizen Kane and Enfants du Paradis and Italian Neorealism. And so on.

But in the 1970s archivists began opening their doors to researchers. Thanks to wider and deeper viewing, new film historians, young and old, were questioning the canon. André Gaudreault and Charles Musser showed that Porter’s Life of an American Fireman, which supposedly gave birth to crosscutting, did not do so; in fact the version people had used for years was a re-cut print! In Jay Leyda’s seminars at NYU, young scholars like Roberta Pearson were tracing what Griffith actually did and didn’t do, a task taken up by Joyce Jesionowski as well. At the same time, Eileen Bowser, Tom Gunning, Noël Burch, and others began questioning the idea that “our cinema” developed step by step from “primitive” beginnings. In England, Ben Brewster, Barry Salt, and others were minutely analyzing changes in film technique in the earliest years. Here at Madison, Tino Balio and Doug Gomery were revising the study of Hollywood as a business enterprise. Specialists working on national cinemas, from Russia, Italy, and the Nordic countries, were showing that there was far more diversity in world cinema than was dreamt of in orthodox histories.

We were part of this generation of revisionists. In the 1970s and 1980s Kristin concentrated on European and American silent film, studying both stylistic movements and film distribution. She also studied particular filmmakers like Eisenstein, Godard, and Tati. I studied European and Japanese cinema. We spent years working on a reconsideration of the history of American studio film in collaboration with Janet Staiger. Writing The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 we realized that asking fresh questions was both necessary and exciting.

That’s what made our task perilous. Everything, it seemed, needed to be rethought.

Most obviously, countries outside Europe and North America had been neglected. Our book was, I think, the first synoptic history in English to make use of statistical information on production and exhibition, and the numbers brought out a striking omission.

In the mid-1950s, the world was producing about 2800 feature films per year. About 35 percent of these came from the United States and Western Europe. Another 5 percent were made in the USSR and the Eastern European countries under its control. . . . Sixty percent of feature films were made outside the western world and the Soviet bloc. Japan accounted for about 20 percent of the world total. The rest came from India, Hong Kong, Mexico, and other less industrialized nations. Such a stunning growth in film production in the developing countries is one of the major events in film history.

Traditional histories, and film history textbooks, had virtually ignored the bulk of film-producing nations. Only one or two major directors would step in from the shadows. Kurosawa summed up Japan, Satayajit Ray stood in for India. And the books’ layout of chapters indicated this second-class status.

The history of film was portrayed as Euro-American, with East Asia, Southeast Asia, South America, and Africa, appearing, if at all, in periods when westerners first got glimpses of their film culture. So Japan was typically first mentioned after World War II, when Rashomon won a prize at the Venice Film Festival. One would hardly know that there were many, and many great, Japanese filmmakers working in a long-standing tradition.

As if this weren’t enough, we were determined to include other varieties of artistic filmmaking. Documentary cinema, animation, and experimental film had attracted subtle historians like Bill Nichols, Mike Barrier, and P. Adams Sitney. We weren’t experts in these areas, but we were keenly interested in the debates in that domain, and so, guided by these and other scholars, we sought to integrate the histories of documentary, avant-garde, and animated cinema into our survey.

1980s-2000s: Kristin and David’s excellent adventure

Kristin at Bonded Storage, Fort Lee New Jersey.

In sum, we decided that we could write a plausible international history of cinema—not a be-all and end-all, but a new draft that reflected the rich variety of new findings and fresh perspectives. Like all historians, we had to be selective. We couldn’t, for instance, track every nuance of the “false starts and detours” in early film technique. More globally, we decided to concentrate on three lines of inquiry.

First, we studied changes in modes of film production and distribution. This inquiry committed us to a version of industrial history. How filmmaking was embedded in particular times and places, how it connected to local culture and national politics: these factors affected the ways films were made and circulated. For example, the early distribution of films followed the trade routes of late nineteenth-century imperialism. That global system started to crack with the start of World War I. A new world power, the United States, became the major film exporting country—a position it has enjoyed for most years since then.

Secondly, we studied changes in film form, style, and genre. We treated these artistic matters as not wholly the products of individual innovators but also as more widely-developed practices and norms. This emphasis on norms allowed us to link, in some degree, the development of technique to opportunities and constraints presented by film industries.

This angle of approach also meant looking at older works with a fresh eye, informed by others’ research but also by our own interests in film as an art. We were obliged to seek out films lying outside the orthodox story. Birth and Caligari and M featured in our account, but so did The Cheat and Liebelei and Assunta Spina (1913, below). In those pre-DVD days, few of the titles we sought could be found on video, but we preferred to watch film on film anyway.

So it was off to the archives. Fortunately, many collections were wide-ranging. We saw Egyptian and Swedish films in Rochester, French and Italian films in London, Indian and Japanese films in Washington, D. C., Polish and African films in Brussels. Committed to documenting our claims with frame enlargements, not production stills, we were lucky to be able to take photos from many of the movies we saw.

In looking at national film industries and artistic change, we wanted to go beyond local observations. So a third question pressed upon us. What international trends emerged that knit together developments in different countries? We could not claim expertise in all the relevant national traditions, but we could, by drawing on films and other scholars’ writings, create a comparative study that gave a sense of the broad shape of film history.

For example, we could point to the emergence of tableau cinema in many countries in the 1910s. We could consider various models of state-controlled cinema in the 1930s and discover the “New Waves” that emerged not only in France but around the world in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Citizen Kane popularized a “deep-focus” look, but comparative study showed us that its principles were prefigured in Soviet cinema of the 1930s and spread to most major filmmaking nations in the 1940s.

Not all trends march in lockstep, but there was enough synchronization to let us plot broad waves of change across the 100 years of film. Our aim was a truly comparative film history.

As a kind of overarching commitment, we wanted readers to think about what historical processes had shaped earlier writers’ frames of reference. How, for instance, did the “standard story” and the mainline canon get established in the first place? Part of the answer lies in the growth of film journalism and film archives. Why did Fellini, Bergman, Kurosawa, and other directors get so much fame in the 1950s and 1960s? True, they made exceptional films, but so did many other directors who remained unknown to a wider public. We suggested that the “golden age of auteurs” owed a good deal to developments in film criticism and to the postwar growth of film festivals.

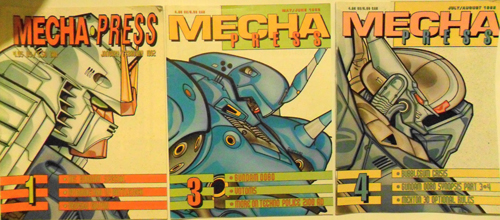

What led Japanese anime to a period of international popularity in the 1980s? Not only worldwide television distribution, but also devoted fans who spread their gospel through videocassettes, the youthful Internet, and such fanzines as Protoculture Addicts and Mecha Press.

In general, the “institutional turn” in film research of the 1970s and 1980s pushed us to consider how film industries and international film culture governed the way films were made and circulated.

The research programs that were launched in the 1970s were characterized by a greater self-consciousness than we had seen before. Historians questioned their assumptions and explanations. Why attribute originality only to “great men” without also examining their circumstances? Why presuppose that film technique grows and progresses in a linear way? To capture this new self-consciousness about purposes and methods, we incorporated something that had never been seen in a film history before: an introduction to historiography. Originally in the printed text, in its latest incarnation it can be found elsewhere on this site.

We also appended to each chapter short “Notes and Queries” discussing intriguing side issues, debates in the field, and topics for further research. Those were put online for download. The third edition’s are here; sample them through the “Choose a Chapter” dropdown menu. The fourth edition’s updates will soon be available.

2018: Results just in

Tangerine (Sean Baker, 2015).

The first edition was published by McGraw-Hill in 1994, a second edition in 2002, a third in 2009—when I wrote the sections you’ve just read. Now we have a fourth edition, published in June. After ten years or so, what’s changed?

We have the same chapter breakdown. Part One deals with Early Cinema, from the beginning to the end of the 1910s. Part Two surveys the late silent era to 1929. Part Three considers the sound cinema up to 1945. Part Four considers post-World War II filmmaking, through the 1960s. Developments from the late 1960s are reviewed in Part Five. The last part deals with the age of New Media, including analyses of changes in Hollywood, the rise of globalization, and the emergence of digital technologies.

We’ve incorporated new lines of research in some early chapters. The chief change involves Alberto Capellani, a director who was little-known before a retrospective at Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna brought many of his works to attention. He worked between 1905 and 1922, making extraordinary films like L’Assommoir (1909) and Germinal (1913), discussed here by Ben Brewster. In the new edition we contrast Capellani’s delicate staging within the shot to the editing-oriented approach of his much more famous contemporary D. W. Griffith. This is the sort of historical contextualizing we’ve striven for in all the editions of the book.

Likewise the availability of films on DVD have enabled us to explore fresh examples of films in the Young German Cinema, the Japanese New Wave, and other movements. We didn’t give up on 35, though. A lot of frames still come from prints. For example, thanks to Haden Guest of the Harvard Film Archive, we were able to obtain a frame from Med Hondo’s extraordinary West Indies.

As you’d expect, the bulk of new material comes in the final stretches. In Chapter 24, we incorporate discussion of The Missing Picture, The Act of Killing, the work of Wang Bing, and the emergence of the animated documentary (Waltz with Bashir, Tower). Our survey of experimental cinema widens to include Liu Jiayin’s work (a favorite of the blog), as well as films by Chick Strand, Marlon Riggs, Phil Solomon (ditto), and Mark LaPore, along with internet experiments like Matt Bucy’s Of Oz the Wizard (2016).

In considering national cinemas outside Hollywood, we catch up with industrial developments in Europe and Russia. Naturally, we take account of new talents, such as Serge Loznitsa and the directors of the Romanian New Wave. The last edition spotlighted many directors still powerful on the international stage, from Almodóvar and Haneke and Denis to Herzog and Varda, but I’m glad we found room for updates on Oliveira and Alexei German, whose beyond-bleak(whose Hard to Be a God (2013) is one of the most tactile films I’ve ever seen.

What do we do with “slow cinema”? We treat it as a development out of classic art-cinema strategies of prolonged duration and “dead time.” We also counterpose it to the nervous “free-camera” style on display in films like Gomorrah (2008) and Toni Erdmann (2016). Our approach to cinema remains comparative, showing how creative alternatives can operate in the same historical period.

DVD availability allowed us to expand our treatment of Nollywood in Chapter 26. There we also trace the emergence of Iran’s Asghar Farhadi (I still admire About Elly) and Cuba’s Fernando Pérez. We’ve especially widened our treatment of Indian cinema, which not only dominates its local market but, in the period since our last edition, has emerged with international successes. I was also happy to learn, thanks to the advice of Lalita Pandit and Patrick Hogan, of the striking films of Rituparno Ghosh. (This hallucinatory scene is in The Last Lear, 2007).

Chapter 27, devoted to Pacific Asia and Oceana, brings those national industries up to date while discussing Taika Waititi, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, and others. Of course we retain considerations of Hou Hsiao-hsien, Hong Sangsoo, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and many other major artists. Our box on Sony, which I always liked, has been exiled to the Notes and Queries online, the better to make room for a box in which we pay tribute to the great Hayao Miyazaki. And of course our section on China has been largely redone, to reflect its rise to international power. We analyze how government officials and private investors leveraged a minor national industry into one of the filmmaking behemoths of our time. Not that it always goes well, as The Great Wall (2017) showed.

Similarly, Hollywood changes so fast that we needed to recast many stretches of Chapter 28’s survey. But the search for synergy across conglomerate domains, the shift from one-off blockbusters to franchises, the impulse toward mergers and acquisitions that marry “content” to delivery systems (cable, the internet): these and other business strategies emerged in even sharper relief ten years after our last edition. Fortunately for our timing, the acquisition of Fox by Disney began while the book was in press, so we were able to sneak that initiative into a new box devoted to the Disney empire. Too bad we didn’t have this frame from Ralph Breaks the Internet: Wreck-It Ralph 2 to illustrate that.

Of course American cinema is more than the studios, so we’ve updated our consideration of indie films, with discussions of auteurs, genres, and trends. (Yes, Wes Anderson and Damien Chazelle are involved.) The third edition considered Mumblecore; now we’ve got coverage of directors like Lena Dunham moving to television and streaming.

Chapter 29, on globalization, runs through several trends that are still with us, from piracy and festivals to diasporic filmmaking and the multiplex strategy. We consider how worldwide fan culture has exposed new possibilities of filmic expression, through mashups, video essays, and DIY exercises like Star Wars Uncut: Director’s Cut (2010).

The chapter also analyzes how countries outside the US are trying to make international hits. The Europeans mostly sought to do this through art-cinema channels, while other countries found some success with popular entertainments. Baahubali 2: The Conclusion (2017) garnered $81 million outside India.

Chinese filmmakers were less reliant on exports, since the stupendous growth of the exhibition sector created a mega-market at home. A hit like Wolf Warrior 2 (2017), which was reported as earning over $850 million, can rival Hollywood’s global revenues within a single territory. Interestingly, the popular successes are often heavily indebted to Hollywood: Baahubali 2 owes a great deal to 300 and other special-effects-heavy spectacles, while Wolf Warrior 2 revives the action style and conventions of Rambo and Mission: Impossible.

For the previous edition, we added a final chapter on digital technology’s impact on cinema. That was as up-to-date as we could make it in the late 2000s, but obviously our treatment needed a big makeover. Drawing on research done for Pandora’s Digital Box, I traced how digital tools entered cinema. For FH 4.0 we update that by tracking the changes in preproduction and postproduction, in early efforts to shoot digital, and then in more ambitious production possibilities, along with internet publicity and marketing. We then cover digital convergence, chiefly through Hollywood’s Digital Cinema Initiative’s effect on theatre conversion and digital production.

Naturally, we also analyze some of digital technology’s effects on film form and style: the possibilities of 3D, the opportunities for longer takes and photographic experimentation, and the new prominence of digital animation. A box contrasts David Fincher, whose embrace of digital yielded new possibilities for classical storytelling, with—who else?—Jean-Luc Godard, whose digital work such as Éloge de l’amour (2001, below) challenges just that tradition.

The convergence story wraps up by tracing how digital distribution, beginning with the DVD and passing through online distribution, arrived at piping films directly to theatres. The chapter ends by looking at how the Internet, video games, and Virtual Reality have interacted with modern cinema.

Our emendations and updates bring home to me the advantages of seeing change against a background of continuity. The film industry replays time-honored business strategies, such as the impulse toward vertical integration. Amazon and Netflix, not content with controlling distribution and (home) exhibition, move into production to assure themselves of a flow of product—just as 1910s exhibition chains created studios to supply their screens. And as I write this, the 1948 consent decrees are being reconsidered as anachronistic.

Likewise, filmmakers of the 2010s confront choices about technique familiar from earlier eras. Since a digital shot can be indefinitely long, when should I cut? I can reframe a shot in postproduction, but I still have to decide on the shot scale. With highly spatialized sound in theaters, where should I locate this effect? Even with new technologies and changing circumstances of reception, the basic demands of form and style persist.

Here’s a taste of our conclusion:

Digital convergence worked hand in hand with globalization and the power of the American studios. The top Hollywood pictures were successful in most countries, and they could be delivered on many platforms. But in the swift media churn, with new formats coming up all the time, would traditional filmmaking die?

Evidently not. For one thing, the number of feature films was surging. In 2002, the world made over 4,000 feature films. In 2016, that number was over 7600. This vast output included blockbusters, modest independent films, and every form in between. The boom took place in the face of home video, cable, satellite, DVD, Blu-ray, VOD, and streaming. It happened despite the fact that a handful of American blockbusters ruled nearly every national market.

But perhaps theaters, the public side of film culture, were in danger? Just the opposite. Screen growth was robust through the 2010s. In 2016, the world had over 163,000 screens. Even without counting the millions of television monitors, computers, and mobile devices, there were far more movie screens than ever before. And plenty of people wanted to visit them. The year 2015 set a record high in worldwide attendance, 7.4 billion admissions. This amounted to about one ticket for every man, woman, and child on Earth.

Digital convergence, boosted by globalization, encouraged the spread of cinema. Personal computers, the Internet, mobile phones, game consoles, tablets, and portable music devices initially could not display films, but all were eventually adjusted to do that. Film wriggled its way into every media device that came along. From broadcast television and videotape to DVD and streaming, films spread beyond the theater. They entered our living rooms and went with us anywhere. Today, more people are watching more hours of motion pictures than at any other time in history. As newer technologies emerge, we suspect that they too will serve the cinematic traditions that have developed over 120 years.

Optimistic, eh? Yep, that’s us. We know that the book is far from perfect, and we’ll be trying to correct mistakes and misjudgments. Still, we hope that Film History: An Introduction tells a story that will encourage young filmmakers and filmgoers to embrace all the traditions of cinema. Those traditions have fascinated us for fifty years, and we hope to communicate some of our enthusiasm to readers.

Film History: An Introduction’s fourth edition is available in several formats, some frankly innovative. To understand why, it’s useful to try to answer the constant question: Why are college textbooks so expensive?

There are plenty of factors to consider, but I want to focus on one: the fact that people can sometimes be rational agents.

The professor rationally decides that she wants her students to read a specific book in order to study aspects of the subject. She assigns it.

Some students will decide to borrow a copy, check out a library copy, or risk not reading the book at all. Those are all justifiable courses of action. But many students, deciding that owning the book will help them succeed in the course, buy it. Still, (a) it’s pretty expensive; and (b) they may not wish to keep it after taking the course. Textbooks are among the few books which users are forced, more or less, to buy.

Many students want to recoup part of their investment, so they resell the book for what they can get. Jobbers and campus bookstores buy the books and resell them to new students. Those folks, themselves rational agents, are glad to get a lower price. I speak as someone who’s bought thousands of used books, including textbooks.

But the publisher and authors reap no rewards from a resale, which replaces the purchase of a new copy. Publishers assume that nearly all purchased textbooks will be resold. Therefore, in order to maintain profitability, the publisher sets the price (wholesale/retail) at a point that will offset at least one future resale.

This has all the marks of an arms race. Publishers raise prices to offset resales, but this gives purchasers a greater incentive to resell, thus flooding the market with more used copies. Publishers also speed up the revision cycle, hoping that new editions will render the old ones less desirable.

The arms race has led to accelerating prices and resentment among faculty and students. Even college administrators have joined the complaint about price rises. (Said administrators aren’t usually inclined to lower tuition, however.) In recent years, the pressure got more intense thanks to two other factors: digital piracy and Amazon.

Start with piracy. Once pdfs of a textbook show up online, publishers suffer big losses. That prods them, as rational agents, to raise the purchase price. (Lowering the price might seem a way to undercut pirate copies that are sold, but you can’t make the book cheap enough to make a difference.) In effect, when somebody buys a textbook they’re helping subsidize someone else’s download. This creates an incentive for rational agents to download the text themselves, thus pushing the price of the physical book ever upward.

As for Amazon: In past decades, the used-book jobbers were quite adroit at distributing used copies to campus stores, but Amazon’s online model proved far more efficient. Moreover, Amazon revived the long tradition of renting books, and the economies of scale made it easy. As rational agents, the Amazonians bought copies from the publisher and then offered them for rent.

Other companies rent textbooks too, on a smaller scale. In all cases, renters are vulnerable to the frailties of human nature. You can read sad stories of renters who failed to return the book in a timely fashion and ran up charges greater than the cost of a straight purchase.

Publishers have responded to Amazon’s rental initiative by launching rental programs themselves. This is what McGraw-Hill has done with our book.

Let’s go through the options. If you go here and then click on “Print/ebook” and “Bundles,” you can see them all.

Film History exists in both digital and print form. The digital edition may be bought or rented. There’s also the option to fold the e-book into a broader platform called Connect, which gives access to online material—clips, links, etc.

The book exists in hard copy as well. It can be rented as a bound volume. Alternatively, it can be bought in a loose-leaf version. (If I were buying it, that’s the format I’d pick.) Prices across all these options range from rentals for $60-$80 and purchase for $118–$130.66 and mixtures of both for up to $150.

What about buying the bound version? As you’d expect, given concerns about piracy and downstream rental or resale, that’s the most expensive option. McGraw-Hill offers bound copies on a rent-to-own basis. As I understand it, the customer first rents the book and if she decides to keep it, she pays the rest of the full price. That price is currently a stupendous $229, but again that reflects the prospect of one or more physical resales.

Anecdotes suggest that film majors hang on to their books and try to build personal libraries. If that’s true, I’m happy, for more than one reason. And I learn that Film History will continue to be sold in bound copies outside North America. In my experience, overseas students don’t complain as much about the cost of books, perhaps partly because they attend schools that have low or no tuition fees.

Would I prefer the old days, when you just bought the book and owned it or sold it or gave it away? As a book collector, I would. But Kristin and I are old, old school; we have thousands of volumes in our library. (Many of those won’t be online in our lifetime.) And we also have dozens of e-books, which are great for ephemeral reading or sturdier research. We recognize that publishing, and authoring, are changing because of technology and social dynamics, and so we adjust. The main thing is to get ideas and information and opinions out there for our readers to consider.

For this edition of Film History: An Introduction, we want to thank the staff at McGraw-Hill Higher Education: our editors Sarah Remington and Alexander Preiss, and their colleagues Jen Thomas, Anju Joshi, and Ann Marie Janette. They have helped us make this edition something we’re very proud of.

Sita Sings the Blues (2008, Nina Paley).

from Observations on film art https://ift.tt/2nfVcZq

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento