Borat Subsequent Moviefilm: Delivery of Prodigious Bribe to American Regime for Make Benefit Once Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2020).

DB here:

Defending some of his wildest films, Hong Kong director Tsui Hark pointed out: “Sometimes it’s fun to be stupid.” True enough. But we need to be stupid in sync. When a leader is being stupid and only some of our fellow citizens are, it’s a lot less fun.

The situation invites you to respond with meta-stupidity: Showing how invincibly stupid others are being by doing something stupid yourself. One option is silly satire (Saturday Night Live), but there’s a more deeply disturbing alternative. You can be stupid in a savage, no-holds-barred way.

This can disturb your audience. Shock defeats geniality, obliterates wit. You get called heavy-handed, on-the-nose, over-the-top, and other hyphenated things. You may even move into the realm of the grotesque.

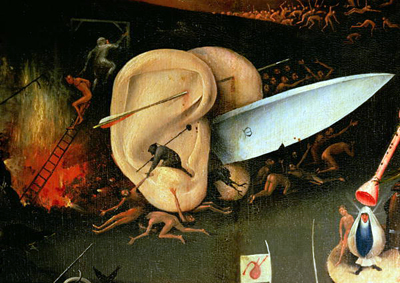

Blunt, tasteless, outrageous grotesquerie has been an important artistic strategy through the millennia. Bosch (below), Bruegel (next), Goya, and other artists have taken exquisite pains to present giddy images of human folly, bursting the limits of taste and sense.

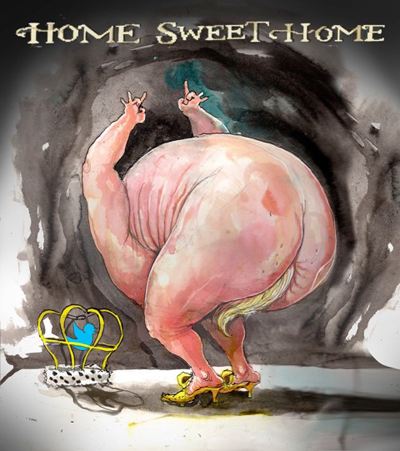

Unsurprisingly, in America the grotesque flourished during the 1960s, in Robert Crumb comix and Paul Krassner’s Disney orgy. Nowadays, Australia’s David Rowe has done fastidious work with slack jaws, skin blotches, and, inevitably, flab.

The realm of the stupid grotesque is one that Sacha Baron Cohen has made particularly his own. It suits our moment.

Friction between parts

The Republican Party’s steamrolling takeover of civil society, begun in earnest in the 1980s but turbocharged under Trump, has created a Golden Age of American agitprop. Responding to the lava flows of vile, vacuous sludge on social media, carefully crafted counterstrikes have shown a fair bit of wit. Call it the spontaneous genius of the American people. That usually comes down to jaunty disrespect.

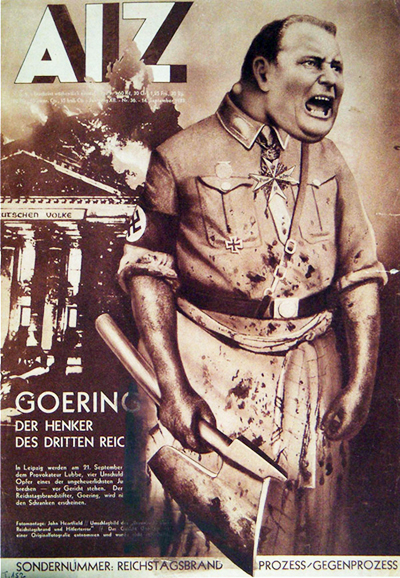

Caricature is the go-to format for those who can draw. But it’s striking that the photomontage techniques of John Heartfield, aimed at an earlier Reich, have been revived for the Age of Trump. Below, Heartfield’s 1933 portrait of Goering as butcher of the Reischstag, alongside an ailing Trump.

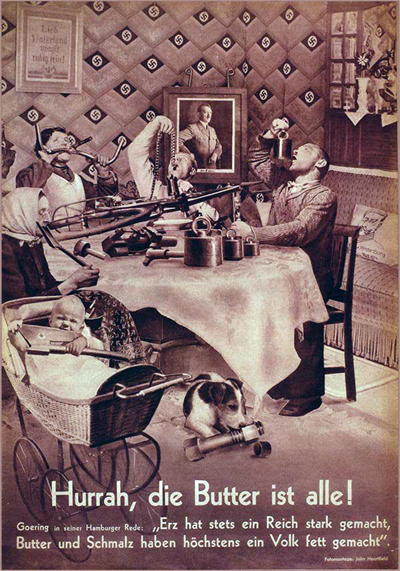

Photoshop makes the craft of photomontage easier than in earlier eras, but the trick is still to have an ingenious idea–a play on words, or a reference to a meme. Heartfield’s famous “Hurrah, the Butter’s All Gone!” defiles the guns-vs.-butter motto of classical economics by suggesting that we’re foolish enough to think we can survive on instruments of death. It also quotes Goering’s speech: “Iron has always made an empire strong, butter and lard have, at best, made a people fat.” While suggesting that Hitler’s followers have a hearty appetite for self-destruction, Heartfield has shrewdly created metaphors: handlebars like a corncob, a bandolier like spaghetti, a bomb like a coffeepot, a grenade serving as a doggy’s bone The baby teething on an axe-blade is a bonus, as are the sprightly swastikas in the wallpaper.

In the gentler example, Trump isn’t just any baby, he’s the kid in Home Alone (covert reference to his cameo in the sequel), with the invaders as both the Blump and, for once, a smiling Bob Mueller.

Note that these aren’t deepfakes, undetectable blends. Montage promotes friction between parts. The juxtaposition bears the traces of the act of bringing disparate pieces together. (Trump’s hands are plausibly small, but that icebag is an awkward fit.) They create a coherent spatial layout, but there’s enough mismatch to remind you of the act of assemblage.

Of course montage is also a film technique, and sometimes–as with the Soviet films of the 1920s, or found-footage films like those by Bruce Conner–we sense a jolt or abrasion between shots. By and large, though, a film like Borat Subsequent Moviefilm: Delivery of Prodigious Bribe to American Regime for Make Benefit Once Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan is less an exercise in montage (despite all its jump cuts) than a faux-documentary mixing the casual norms of prosumer video and quickie tabloid-crime cable fodder. Perhaps the worst-directed major film of 2020, it has its compensations. Instead of the relatively softball treatment of POTUS seen in my images, Borat Subsequent Moviefilm gives us something much closer to Heartfield’s blood and bombs. As in a photomontage, bits of reality are turned into a cartoon that’s outrageous, even offensive. But like Heartfield, Baron Cohen reminds us of one crucial point. Fascism, like stupidity, can be fun.

Just another movie?

Spoilers ahead, of course.

The grotesque is usually associated with deformation, but Borat Subsequent Moviefilm has a firm structure. At the risk of sounding silly, I insist that it’s a surprisingly tightly-knit classically conceived film.

The hero starts off with a goal. Ex-journalist Borat Margaret Sagdiyev will get a reprieve from penal labor if he will deliver Johnny the Monkey as a bribe to well-known “pussy hound” Mike Pence. Borat’s daughter Tutar joins Borat in the US by smuggling herself into Johnny’s cargo crate, and because she has eaten Johnny, she must replace him as Pence’s bride.

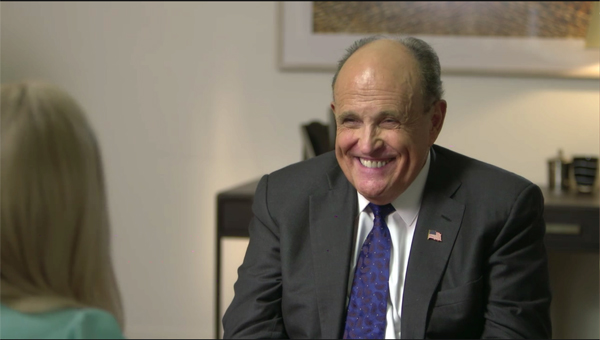

The film falls into the familiar four parts. The setup introduces Borat’s goal and peaks at the invasion of CPAC. As usual, the development section that follows redefines the initial goal. Turned away by Pence’s guards, Borat gets his boss’s permission to offer Tutar to Rudy Giuliani instead. This goal forms the through-line for the rest of the film, as Borat undertakes to make over Tutar into a submissive American woman.

The third section is occupied with various delays and stretches of character change. Tutar starts to liberate herself from Kazach patriarchy and Borat comes to accept his daughter as a person. At the climax, when Tutar decides to offer herself to Giuliani to save her father, while he races to rescue her–prepared to sacrifice himself to save her from violation. The epilogue celebrates a new stability with a happy ending, if a worldwide pandemic counts.

The main thread is the familiar device of the naive traveler, the alien who reminds us of how strange our everyday world can seem to an outsider. Borat is introduced to smartphones (though he never figures out the camera), cyberporn, plastic surgery, QAnon, and Covid-19. Tutar learns that her vagina will not chomp her arm, that women can drive cars, and that fathers can walk hand in hand with their daughters.

As in a traditional film recurring motifs–raw onions, a chocolate cake, a plastic baby, strings in the brain–bind the scenes together. Stylistically, the apparently offhand shooting displays classic camera ubiquity. We always have the best view because multiple setups are covering the action (something not common in a true documentary), and probably scenes are retaken. Matches on action are the giveaway.

Many of the scenes, particularly those involving crowds at right-wing events, are made to cohere through the Kuleshov effect. Editing allows Pence to appear to react (stonily) to Borat’s appearance in a Trump fatsuit at the back of the hall.

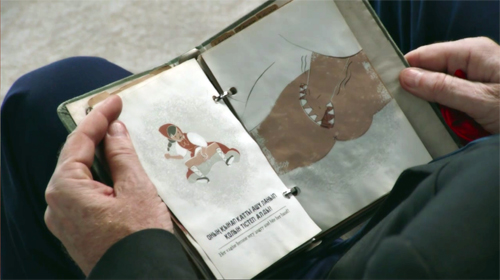

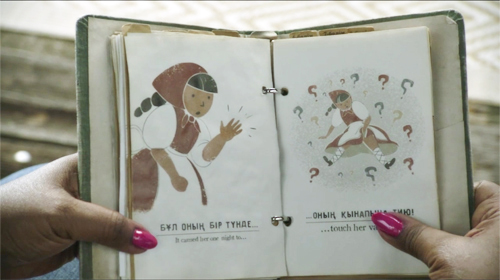

Think Rudy really inspected these pages of Tutar’s book? He is very moved by receiving it.

And there’s a nice homage to Griffith-style crosscutting, when Borat scrambles to rescue Tutar from the clutches of America’s Mayor.

I grant that Borat Subsequent Moviefilm seems pretty episodic when you watch it, but I suspect that’s partly because of the inherent looseness of a road-movie plot, and partly because of the shock effect of individual scenes. That shock depends, I think, on the relentless grotesquerie on display. Classical clarity of presentation enables the film to chart two major types of stupidity at large in our world.

Leering in bestial degradation

The aesthetic of the grotesque centers on fanciful but disturbing deformation, an exaggeration that’s at once playful and threatening. Art critic John Ruskin, describing the carved heads he found on the Bridge of Sighs in Venice, was appalled to see them “leering in bestial degradation.” That’s not a bad description of Borat Subsequent Moviefilm. The operative word, of course, is leering. The grotesque, as James Naremore points out, mixes fear, disgust, and laughter.

The grotesque breaks categories. Borat’s main disguises as a spare-tired redneck make him implausibly cartoonish. Animals become human (Johnny the chimp is a porn star) and humans become animals, or simply raw material. The producer of Borat’s previous film has been turned into an armchair, with privates preserved.

Species transmogrify. Borat himself–hugely tall, loping like a moose, shitting in front of Trump Tower, with his inane grin and wobbly vocal pitches, high-fiving with hands like seal flippers–is a walking graffito, something you might see scrawled on a remote East European grotto. Tutar, like all Kazakh daughters, is kept in a cage. Grotesque art also breaks taboos. The film wallows in menstruation, incest, masturbation, animated POTUS erections, kinky birth stories, and sex toys, including a gag that pivots on Borat’s accent (Amazon delivers “fleshlights” instead of flashlights). In this context, Rudy Giuliani’s 1200-watt smile becomes wolfishly sinister.

Again, though, narrative processes provide some development. Tutar abandons her cage and (in a sign that Borat is warming to her) joins her dad in the trailer. She becomes a high-gloss Fox-babe interviewer. Borat correspondingly submits to a gender revision, showing up in a bikini to save her from Giuliani. The armor-plated gender roles assigned by Kazakh culture melt a bit in Borat’s odyssey, though again–faithful to the grotesque–father and daughter’s final slow-mo romp through Washington streets is less a lyrical reconciliation after two “character arcs” complete than another bit of tawdry public cosplay.

Eisenstein thought that the grotesque had two registers, the comic (say, slapstick) and the pathetic (say, The Hunchback of Notre Dame). So you could argue that the Borat film moves broadly from the first to settle on the second. In the very last scene, there’s even a hug as a “normalized” Tutar and Borat assume meritocratic professional identities.

Still, this normalization doesn’t really wipe away a cruel Boschian vision of a hellscape seething with grotesques. The film sets up two parallel cultures, Kazakhstan and the USA, each deeply committed to imposing stupidity on its populace.

Kazakhstan is a parody of traditional folk patriarchy as recast by a Communist state. Fathers treat daughters as livestock while corrupt officials execute their enemies. Social life is ruled by a guidebook that Tutar dutifully carries everywhere. It details all the powers due to men and all the roles allotted to women, with special instructions about areas they must not touch.

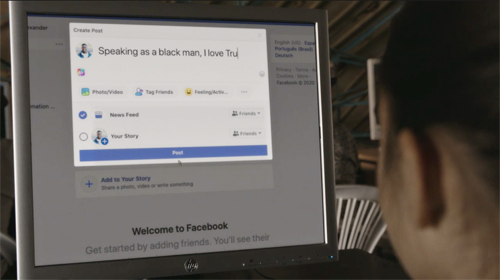

The USA, for all its wealth, is filled almost completely with deadpan imbeciles who advise Borat on how to cage his daughter and gas gypsies. Women instruct Tutar in finding a sugar daddy and behaving at a debs’ ball. True, Tutar learns that the Kazakh manual is bunk, but her new vessel of truth is Facebook, which assures her that the Holocaust didn’t happen.

Armed only with a barbaric yawp, Borat visits anonymous malls and bland bakeries. This moronic inferno houses the pious women of a Republican club, the well-heeled attenders of a CPAC meeting, and the Gadsden flag-wavers. As the virus spikes, Borat takes refuge with conspiracy theorists who claim that the Clintons drain children’s adrenaline and feast on blood. Crashing a Second Amendment rally, Borat can quickly teach the audience a song which urges that members of the press be chopped up “like the Saudis do.”

Does an elderly Jewish woman provide a glint of light? After all, she assures Borat that the Holocaust really happened. But the twist is that he’s comforted because her news vindicates his countrymen’s historic role working in the camps. And the image remains pure grotesquerie: a Nosferatu-like Borat measures the lady’s nose, in an echo of the visit to the obliging plastic surgeon who discusses Jewish noses.

If the Kazakhs have been regimented in the service of the state, the American social default is freewheeling, blank indifference. You can tell someone you’re chaining up your daughter, you can send a penis image by fax, you can walk into a conservative gathering in KKK robes, and at best people raise an eyebrow. Stupidity is stolidity. Behind every reaction shot is the unspoken American version of tolerance: Whatever.

The French call us les grands enfants, the big kids. In a country where you do whatever you want until somebody says you can’t (and then you will demand to do it as an expression of freedom), why shouldn’t a man suggest paying for breast implants by letting perverts watch the procedure? (“The perverts,” the staff member explains, “have to be medical personnel.”) Why shouldn’t a birth counselor overlook the father’s apparent confession of impregnating his daughter? You want “Jews will not replace us” squiggled on a cake, with a happy face underneath? No problem. Why shouldn’t the President’s personal lawyer claim on the record that the Chinese invented the virus and deliberately unleashed it on the world? Maybe. Might be something to that. I’m just saying. Check out the retweet.

The most redemptive moments come with Jeanise Jones. As Tutar’s babysitter she nudges the girl away from having breast implants and sets her on the way to thinking independently. Jeanise also teaches Borat that the pain he feels in his heart is love for Tutar. Another way this is a classical movie: Borat Subsequent Moviefilm has its own Magic Negro.

Narrative being narrative, the climax brings a change. Borat returns home, expecting execution, but he learns that his mission has actually been accomplished. He learns that his real purpose was to spread the coronavirus, developed in Kazakh labs to punish the world for laughing at the homeland after his first film. He has been the Typhoid Mary of the pandemic (his middle name is Margaret), and with his success Kazakhstan recovers a place of honor in the world community. It has moved forward to the digital age. Instead of playing ostrich, cut off from the outside world, the people are now staffing troll farms.

Now the daughters have joined globalization and have something important to do: overturn American democracy.

And instead of the Running of the Jew, the honorable tradition revealed in the first film, the homeland can afford to look down on a new scapegoat: America. In a colossal magnification of the grotesque, the ballcap hillbilly and the gun-toting Karen terminate Dr. Fauci.

Satire gone gross, pranks and punking pushed to randy delirium: No wonder Sacha Baron Cohen was so suitable for the role of the Yippie Abbie Hoffman in The Trial of the Chicago 7. In Borat Subsequent Moviefilm, I think he has done something important. He has made the 1960s put-on a vehicle of political criticism, by simply demonstrating how scary the pleasures of being stupid can be.

The movie cons its subjects, people say. No, they con themselves, aided by the Whatever principle. It’s not always very amusing, detractors say. Right. The grotesque never is. Being thoroughly stupid isn’t thoroughly fun. We are going to learn this over and over in the days and years ahead.

For enlightening commentary on Heartfield, visit here. On comix, the authoritative source is James P. Danky, Underground Classics: The Transformation of Comics into Comix (Abrams, 2009).

The standard survey of the grotesque is Wolfgang Kayser’s The Grotesque in Art and Literature. Jim Naremore makes the case for Stanley Kubrick as an artist of the grotesque in On Kubrick (British Film Institute, 2007). My quotation from Ruskin comes from p. 26 of that.

On the camera-ubiquity convention of pseudo-documentary, as it bears on The Office, you can see this entry. There’s also this one, on the Paranormal Activity series.

A noun, a verb, and . . . copping a feel in Borat Subsequent Moviefilm.

from Observations on film art https://ift.tt/3jLQDRp

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento