In the final moments of Sofia Coppola’s 2003 movie Lost in Translation, the quixotic romantic connection between Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson) and Bob (Bill Murray) culminates on a crowded Tokyo street not with a kiss—though there is one—but with a whisper.

Leaning close, Bob says something in Charlotte’s ear. Something, but we don’t know what. Coppola, who also wrote the screenplay, leaves it up to us, permitting us to project our own private fantasies onto those muffled words. The private, unknown, ungraspable quality of the final exchange—after we’ve been privy to such intimacy between the two characters—gives the closing a greater poignancy: it’s a bittersweet reminder that something has ended.

If you consider that moment in light of Coppola’s luminous debut film, The Virgin Suicides (1999), an adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides’s celebrated 1993 novel, its significance deepens. In the hazy, dreamy, poisonous world of The Virgin Suicides, language is limiting, even imprisoning, while greater, more profound truths lie beyond narration, in the visual, in the experiential, the imaginative.

“With a book like this, no one should really play the characters,” Eugenides once mused when asked about the adaptation, “because the girls are seen at such a distance. They’re created by the intention of the observer, and there are so many points of view that they don’t really exist as an exact entity . . . I tried to think of the girls as a shape-shifting entity with many different heads. Like a hydra, but not monstrous. A nice hydra.”

Indeed, Eugenides’s novel explores the many ways boys try, and fail, to understand girls—or, more largely, an essential femininity that seems forever just beyond their grasp. The story is told through a kind of collective narrator—a group of men, now approaching middle age, who are haunted by an episode from their youth in suburban Michigan during the 1970s, when the glamorous Lisbon sisters, a source of captivation for the boys, took their own lives. As the narrator attempts to make sense of the sisters’ lives and deaths, we see unfurl a glorious romantic tapestry stitched together from the boys’ imaginations, speculations, private fantasies. Underlying Eugenides’s tale is the understanding that their knowledge is only ever partial and that, ultimately, rather than constructing a history of the Lisbon girls, they are excavating their own histories, and the things lost between their wide-eyed adolescence and their sad, “soft-bellied” adulthood.

Coppola has said that, for her, The Virgin Suicides is about “how deeply people can affect you, and how little images can get the biggest importance, and never go away” (emphasis mine). Restricting the novel’s fulsome, extravagant, word-full storytelling to the voice-over (provided by Giovanni Ribisi), she infuses her film with images—impressionistic, unnarrated peeks into the sisters’ world on its own terms. In so doing, she exposes the tragic chasm between the narrator’s assertions about the sisters (what they represent, how they might be “diagnosed”) and the sisters’ actual private experience. And, while the majority of the movie consists of following the boys’ gaze, Coppola is determined, too, to show us what they can’t see, what they misunderstand, what they simply miss. By the closing shots—following the girls’ desperate final effort to escape their imprisonment at the hands of their parents (Kathleen Turner and James Woods)—the gulf between what we hear and what we’ve seen feels immense, impassable.

It is only appropriate, then, that the movie opens with an image and no words. Before the voice-over begins, we “meet” blonde and lovely fourteen-year-old Lux (Kirsten Dunst), eating a red Popsicle on a leafy suburban street. It’s a familiar Lolita-esque tableau, but one that Coppola immediately upturns. Instead of suggestive mouth play, a come-hither look, Coppola’s Lux chomps heartily, finishing the Popsicle in a few bites, and, with a quick, private smile, walks offscreen and away from our salacious gaze. The next shot is of an old man watering his lawn, the hose a suggestive geyser erupting from between his legs.

From the start, then, we see that the standard narratives, the endless cultural fantasies about teenage girls, are going to be played with, refused, subverted—a point driven home in the shot just after the opening title, in which the screen fills with Lux’s image, superimposed, godlike, across the sky as she gazes into the camera (and us) and winks.

Likewise, Coppola assures us from the moment they’re introduced that her Lisbon sisters are not Eugenides’s “hydra” but five distinct young women. One by one, the camera freezes on the girls as they exit the family car. As we focus on them, their unique signatures flash across the screen, from Bonnie’s comic-book-round letters to Mary’s graffiti-puffed ones, from the stars over Cecilia’s i’s to the slash under Therese’s name and the heavy-metal lightning bolt under Lux’s. Coppola demands that we see past the scrim of the male narration and to each sister’s specificity.

By this point, the voice-over narration has begun, and it will continue, heavily, through the rest of the movie. As in the novel, the narrator attempts to control the story, to overlay interpretations, to proclaim meanings and attribute intentions. For him, for all these boys, the Lisbon sisters are hothouse flowers, girls behind glass, with the boys as thwarted white knights. This is courtly love, with all the chasteness and objectification the term implies, and its primary purpose is not to honor or understand the Lisbons but to glamorize and romanticize the boys’ own longing.

Coppola, however, is less interested in these fantasies than in the sisters’ harsh reality: the misery of their mother’s oppressive rules, their father’s impotence, the smothering feeling of their home, its wall-to-wall carpet sometimes seeming to swallow them up. Consistently, she pairs the voice-over with visuals that undercut or contradict it, or that remind us what we’re missing. And, in so doing, she shows us how all those words only take us further and further away from truth, experience, understanding.

This dynamic is something that, on some level, the boys themselves recognize: access to one of the girls’ language—through Cecilia’s diary—brings them no closer to her experience. They’re flummoxed by it—at least momentarily, until they begin to develop theories and even psychiatric diagnoses (today, we might call it “boysplaining”). Armed with all this new “data,” the narrator says, in a passage drawn very closely from the novel, “we felt the imprisonment of being a girl, the way it made your mind active and dreamy, and how you ended up knowing what colors went together. We knew that the girls were really women in disguise. That they understood love and even death, and that our job was merely to create the noise that seemed to fascinate them.”

But the diary passages don’t actually demonstrate precocious wisdom, nor girls in thrall to the “noise” of antic boys (boys are barely mentioned). Instead, they show a mind occupied by sisterly rivalries, unfortunate family dinner options, and the sisters’ own idiosyncratic interests (in the case of Cecilia, whales and dying trees; in Lux’s, her crush on the garbage collector). Further, the diary entries highlight the girls’ distinct personalities (Mary’s self-dramatizing, Lux’s lovesickness, Therese’s bullying, etc.). It is, after all, no coincidence that the girls all choose different modes of suicide (Cecilia jumps out a window, Bonnie hangs herself, Mary puts her head in the oven, Therese takes sleeping pills, Lux asphyxiates herself in the garage). If the boys refuse them their identity, they’ll assert it in the only way they have left: death.

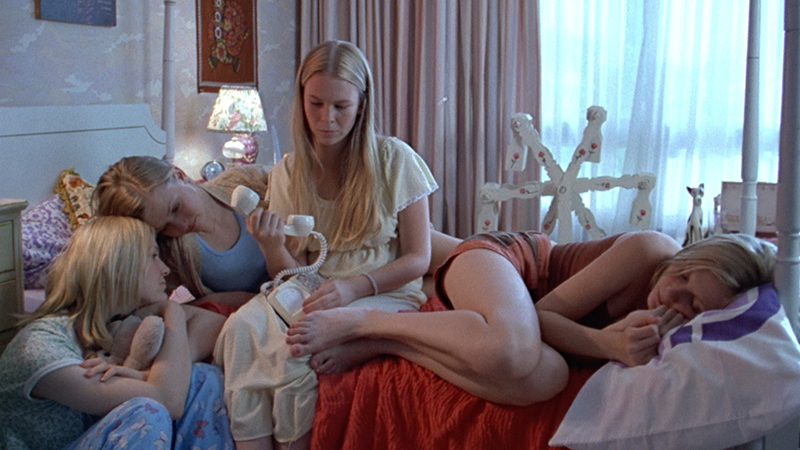

If the novel and the movie’s structure are about boys telling, Coppola’s visual strategy is about girls showing. Increasingly, as the story unfolds, she lets us behind closed doors in ways that are beyond the boys’/narrator’s imagining. The private, unglamorous, unlovely moments. The pain (of Cecilia’s despair, of Lux’s heartbreak). In a series of visuals—those “little images” that have the “biggest importance, and never go away”—we see these are real, living, breathing, sweating, menstruating girls. We see them painting their toenails, lounging in the candy-colored sloth of their bedrooms and bathroom, being bored, playing with their tangled rubber bands and plastic bracelets, poring over fashion magazines and travel catalogs, rolling their eyes over boys. We see them messy, unhappy, yearning, petty, aroused. We see their desire, foremost the desire for Trip (Josh Hartnett) of Lux, who nearly devours him in a stolen make-out session in his car. And the girls’ realness, for Coppola, is glamorous, is mysterious and complicated—a theme she will extend through many of her films to come, including her 2017 gothic tale of female desire, The Beguiled.

All of these insertions and interventions accumulate, and culminate, at a key moment late in the film that diverges, delicately but devastatingly, from the novel. Both the book and the film hinge on the night of the homecoming dance, the night Lux and Trip consummate their attraction on the school’s football field. It is this fateful incident that leads the Lisbon parents to pull their daughters out of school and make them virtual prisoners in their home, an imprisonment that provokes the suicides themselves.

In Eugenides’s novel, we learn of Lux and Trip’s encounter secondhand, and only from Trip’s point of view (as told to the boys)—a cold, abbreviated rendering. Twenty years older now, he recalls a fairly mundane conversation the two of them had as they walked across the football field, and, in a few brief lines, sums up the highly anticipated consummation: “Throughout the act, headlights came on across the field, sweeping over them, lighting up the goalpost. Lux said, in the middle, ‘I always screw things up. I always do,’ and began to sob.” That’s all we learn about the sex itself. The boys ask Trip what happened next: did he put her in a cab? But Trip says no, adding, “I walked home that night. I didn’t care how she got home. I just took off . . . It’s weird. I mean, I liked her. I really liked her. I just got sick of her right then.”

As we read the passage, we’re meant to feel for Lux. Or, more accurately, we try to imagine her feelings. But in the movie, Coppola insists we do more than imagine; she insists we experience Lux’s aftermath with her. We see what is unnarrated, inaccessible to the boys. We watch as Trip leaves a sleeping Lux, and then, in a high-angle long shot that takes in the entire football field, we watch Lux wake in the fuzzy blue dawn, alone. In sharp contrast to our first views of Lux—dominating the screen, grinning, Popsicle in her mouth, and, later, filling the whole sky—she looks so small and forlorn. And Coppola stays with her, painfully, drawing the moment out as Lux reaches for her shoes, her homecoming tiara, struggles to put them on, looks around helplessly, a tiny white figure at the bottom of the frame. A child, a ghost.

And Coppola is not done with us yet. We watch Lux in a cab, face leaning against the window. We watch her arrive home and face her hysterical mother, who grabs her by her maw. We experience all of it, the disillusionment, the humiliation, that knife-sharp coming-of-age moment when you realize love isn’t forever and people will disappoint you.

It’s only then that Coppola cuts to the older Trip (Michael Paré), who recalls, slightly less harshly than in the book, “I didn’t care how she got home. It was weird. I mean, I liked her. I liked her a lot. But out there on the field, it was just different then. That was the last time I saw her.” He pauses before adding, “You know, most people will never taste that kind of love. At least I tasted it once.” These final lines appear in the novel at an earlier, more ruminative moment, but by dropping them in here, Coppola emphasizes their essential solipsism.

In the novel, we learn much earlier that the older Trip is in rehab, but Coppola saves the revelation for this moment, further undercutting Trip’s self-serving, self-romanticizing gloss and the smirk that follows. It would be hard not to read this choice as Coppola trying to balance the scales, to strip Trip of the last of his unearned glamour, this aging high-school heartthrob who treated Lux so shabbily. Who wanted only the fantasy of Lux, not the reality. Who wanted only the projection, not the truth. The preceding episode, Lux’s private aftermath, brings us closer to her than the boys ever manage to get. And, if Lux appears as a ghost on that football field, she nearly is one through the rest of the movie, a figure hovering in the background until the night of her death. But Coppola gives her the last word—and it’s not a word, of course, but an image.

The film’s closing moments show the boys, months after the suicides, standing across the street from the now-empty Lisbon house as the voice-over bemoans how the girls “hadn’t heard us calling, still do not hear us calling them out of those rooms, where they went to be alone for all time, and where we will never find the pieces to put them back together.” As we hear these words, Coppola’s camera shifts from matching shots of the watching boys and the house to a sidelong view of the boys alone, their gazes directed offscreen. You’re focusing on the wrong thing, she seems to be telling them, telling us. Look here instead. The camera then diverts our gaze away to show us what the boys are failing to see, to understand: this isn’t their story, it’s the Lisbons’.

In the movie’s final gesture, the camera tilts slowly up into the sky—the same sky where, in the film’s opening, we saw Lux’s face superimposed, godlike, all-knowing, knowing us. This time, however, Lux’s face does not appear, obstructed by the dying trees, the power lines. It does not appear, but if we’ve been watching, we feel it nonetheless.

Megan Abbott is the Edgar Award–winning author of eight novels, including Dare Me, The Fever, and the best-selling You Will Know Me. She is a staff writer on HBO’s The Deuce. Her next novel, Give Me Your Hand, comes out in July 2018.

from The Criterion Current https://ift.tt/2K9mScK

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento