For Yuri Tsivian

DB here:

Everyone knows Eisenstein as a theorist and practitioner of something called montage, which in his hands comes to mean a lot of things. But he was no less interested in what he called expressive movement. He believed that the viewer could be aroused by dynamic physical action that carried powerful feeling. Expressive movement pervades the set-pieces of his silent films. On the Odessa Steps of 1925’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), we get the robotic descent of the Cossacks opposed to the agitated flight of the citizenry, and the street massacre of October (1927) makes even mechanical bridges seem ferocious. But even less flamboyant moments, from the animalistic antics of the spies in Strike to the weeping masses at the Odessa quai, are full of expressive postures, gestures, and expressions. Eisenstein sculpts the human body so as to project extreme states of feeling.

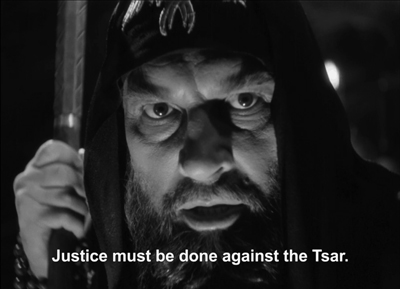

That effort is on full display in Ivan the Terrible Part II, which I discuss in our current entry on FilmStruck‘s Criterion Channel. My comentary builds on an analysis I offered in my book The Cinema of Eisenstein, but the clever experts at Criterion have created dynamic juxtapositions through cutting and replays that I couldn’t summon up in print. I try to show how, as ever, Eisenstein sacrifices bland realism of behavior to something more sharp and intense. In this “theatrical” film, he goes beyond line readings to offer maniacally heightened physical action–a sort of deadly serious, amped-up, live-action cartoon. Eisenstein worshipped Disney, after all.

Today’s blog entry bounces off that installment to show the connection between expressive movement and the most banal stock-in-trade of cinema: the standard scene of two people talking to each other.

Lessons with the master

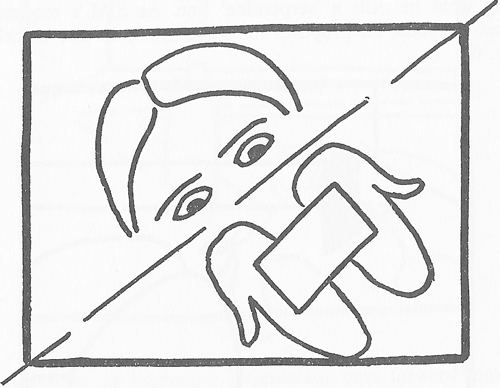

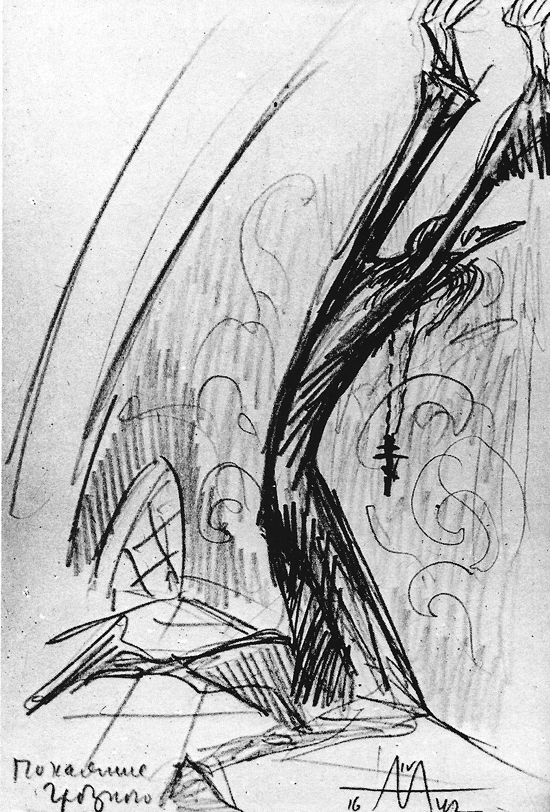

A sketch from Eisenstein’s lectures on Crime and Punishment.

Eisenstein’s silent films seek a “dramaturgy of film form” that would surpass traditions of theatrical and novelistic storytelling. This mission, which creates a sort of epic cinema, left an odd gap. From Strike (1925) to Old and New (1929), his films are notably lacking in one stock ingredient. He seldom creates sustained scenes showing a developing conflict between two characters in an ordinary setting–a parlor or office or street. With few exceptions, Eisenstein “explodes” even standard scenes by cutting to action elsewhere. The factory owners of Strike chortle over drinks while, thanks to parallel montage, the workers are rounded up by soldiers on horseback.

Other Soviet Montage directors were willing to work up theatrical scenes: Pudovkin has a Hitchcockian suspense sequence in Mother (1926), while Kuleshov turns the second stretch of By the Law (1926) into a Kammerspiel. But Eisenstein’s urge to splinter face-to-face dramaturgy came from a different sense of theatre–that “Theatricalism” of his teacher Meyerhold, who saw the stage not as the copy of a real space but as an arena for performance. Eisenstein extended this idea by thinking of the shot and the sequence as an arena for action, specifically expressive movement.

By the 1930s, Eisenstein may have sensed that sound cinema would make films more theatrical in a traditional sense. Sequences would be more concentrated in one locale and focused on a few characters. Crosscutting, a mainstay of silent film, would become rarer. He accordingly began to ponder creative ways of filming two-handers. In his courses at the Soviet film school VGIK he explored ways to intensify dramatic face-offs without interruptive cutting.

These lectures are inspiring because they show you a filmmaker thinking through problems and tracing how one solution leads to new problems. A soldier returns from the war to find his wife pregnant with another man’s child. With his students Eisenstein spent weeks scrutinizing options for performance, shooting, and cutting this simple situation. A banquet is held for Dessalines, Haitian hero. How do you film his realization that his hosts are planning to kill him? How do you present the bedroom of Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, or the claustrophobic apartment of Thérèse Raquin? How do you stage Raskolnikov’s murder of the pawnbroker in Crime and Punishment…and do it in one fixed shot? (You don’t hear much about Eisenstein the long-take man.)

The results of this line of thinking show up in his films. Alas, we have only glimpses in what remains of Bezhin Meadow (finished 1937; banned, now lost). And Alexander Nevsky (1938), still conceived on a broad canvas, doesn’t really face up to the demands of intimate scenes. It’s only in both parts of Ivan the Terrible (1944, 1946) that we can see how Eisenstein plunged into doing what most directors do: filming uninterrupted scenes of people talking to one another.

Needless to say, he doesn’t do it the way they do.

The tsar in your lap

Expressive movement is involved, but so too are other stylistic strategies. For one thing, Eisenstein rethinks analytical editing. Characters need not face one another; they can be turned to the viewer and interact by shifting their eyes. No need for over-the-shoulder reverse angles either; you can cut in or out along the camera axis. Both strategies are introduced at the start of Ivan the Terrible Part I.

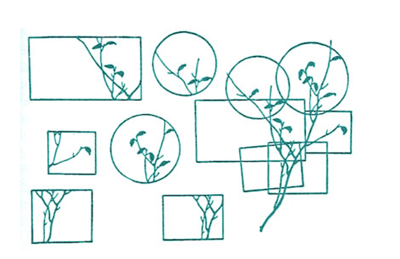

More elaborately, Eisenstein may dissect a scene through what he called in his VGIK classes the “montage unit” (uzol), a cluster of shots taken from roughly the same orientation. These yield chunks of space that overlap when edited together. He diagrammed this procedure in an illustration of cherry blossoms he found in a Japanese drawing manual.

This collage of overlapping bits, anticipating Hockney’s photo paste-ups, is actualized on film in the Pskov sequence of Ivan Part I, as I discuss in my book.

Another strategy is the use of depth. While Renoir, Welles, William Cameron Menzies, and other directors were trying out deep-space staging and depth of camera focus, so was Eisenstein. Well before Welles, he and his Soviet colleagues offered grotesque wide-angle shots. Below, Old and New and China Express (Ilya Trauberg, 1929).

More rigorously, Eisenstein began to think of how to arrange his scenes along the camera axis. True, a great many of his scenes are staged laterally, with figures arrayed from left to right.

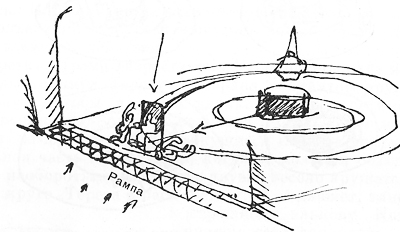

But others, particularly those at a dramatic pitch, are staged in depth. And what distinguishes Eisenstein, to my mind, is a strikingly confrontational or immersive approach. You can see it emerging in the VGIK exercises, notably in his stage designs for a hypothetical production of Thérèse Raquin. Here the paralyzed, speechless Madame Raquin terrorizes the murderous lovers with her glittering eyes. Eisenstein wanted the actors to perform on a turntable that would show her chair rotating to spy on the couple’s affair from different vantage points. At the climax, when the guilty lovers commit suicide, Madame Raquin’s chair was to break from the circle and propel itself forward, so that she would be staring furiously into the audience.

This might look gimmicky, a sort of stage equivalent for what we can easily accomplish in cinema. Don’t directors often heighten the drama by making their actors advance to the camera? But in many scenes Eisenstein moves his players toward us, then cuts further backward, letting axial cuts create an unfolding foreground. A new playing space is opened up, and the actor is free, or rather compelled, to thrust further forward, sometimes into uncomfortably big close-up.

The Soviets called axial cuts “concentration cuts,” and we mostly find them used to enlarge, usually shockingly, something far off. But Eisenstein creates something more unusual and risky.“In my work,” Eisenstein wrote, “set designs are inevitably accompanied by the unlimited surface of the floor in front of it, allowing the bringing forward of unlimited separate foreground details.” In principle the foreground could unfold forever.

The result sometimes yields direct address, as in my Criterion Channel example, but more generally it creates a sense of characters passionately engaged in clamping their will upon others and hurling themselves not just at one another but at us. Characters confide in the camera, and–long before all today’s talk of “immersive” cinema–the camera is us.

The short lesson is that we still have a lot to learn from Eisenstein–and his films. Apart from opening up new vistas of cinema, they offer thrilling experiences. Ivan Part II, subtitled “The Boyars’ Plot,” is a dark Jacobean drama of bloody revenge and betrayal. It’s twisted enough to satisfy any connoisseur of palace intrigue. It’s also brilliantly weird as cinema. Once more the Old Man comes through.

Thanks as ever to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and their colleagues at Criterion for the making this installment, which was a bit tougher than usual. Thanks as well to old friend Erik Gunneson. Our entire Criterion Channel series is here.

The best source for Eisenstein’s VGIK classes remains Vladimir Nizhny’s Lessons with Eisenstein, my pick for one of the top ten film books ever published. Direction, Volume 4 of Eisenstein’s Selected Works in Six Volumes (Izbrannie proizvedeniia v shesti tomakh, 1964-1969) is the source of other examples I use here, including Thérèse Raquin, from p. 622.

Of the immense literature on Eisenstein, I especially recommend Yuri Tsivian’s monograph on Ivan the Terrible in the BFI series. Kristin wrote a whole book on Ivan: Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible: A Neoformalist Analysis.

I discuss Eisenstein as an action director in an earlier entry. On axial cuts in Eisenstein and others, go here; Kurosawa’s use of them is discussed here.

Hockney’s photomontage Mother 1 is from 1985.

Also, too: I noted earlier that my book On the History of Film Style has gone out of print. An e-book edition, with updates and color images, is nearing completion. I hope to offer a pdf to you soon. Yes, Eisenstein is involved.

Eisenstein sketch: Ivan pleading for mercy in the Last Judgment, planned for Part III of the film.

from Observations on film art https://ift.tt/2HGzIgZ

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento