I Programmi in tv ora in diretta, la guida completa di tutti i canali televisi del palinsesto.

from ComingSoon.it - Le notizie sui film e le star https://ift.tt/3d3a7xR

via Cinema Studi - Lo studio del cinema è sul web

I Programmi in tv ora in diretta, la guida completa di tutti i canali televisi del palinsesto.

I Programmi in tv ora in diretta, la guida completa di tutti i canali televisi del palinsesto.

I Programmi in tv ora in diretta, la guida completa di tutti i canali televisi del palinsesto.

Un americano in un paese del Sud-est asiatico: cronaca di una lavorazione turbolenta e di una storia quasi vera.

No Escape - Colpo di stato è un thriller politico che il regista John Erick Dowdle e suo fratello Drew, produttore del film, hanno orgogliosamente definito un B-movie, non solo per il basso budget, ma anche per certe situazioni estreme da horror in cui si trova il protagonista che lo accostano a notevoli esempi della categoria. Al centro della vicenda c'è una famiglia americana che capita in un luogo magari giusto ma nel momento sbagliato. Un signore di nome Jack Dwyer, che è un imprenditore statunitense dipendente da una società specializzata in sistemi idrici, si trasferisce in un paese indefinito del Sud-est asiatico insieme alla moglie e alle figlie per lavorare presso l'acquedotto locale e finisce per trovarsi nel bel mezzo di una sanguinosa rivolta. A interpretare questo personaggio è, sorprendentemente, Owen Wilson, attore comico per eccellenza che torna al dramma a ben 14 anni di distanza da Behind Enemy Lines. Al fianco dell'Hansel McDonald di Zoolander troviamo Pierce Brosnan, nei panni di un eccentrico inglese che aiuterà il nostro eroe. La lavorazione del film, girato in Thailandia, è stata molto difficoltosa e Wilson ha rischiato addirittura di finire in gattabuia.

Tanto la trama di No Escape quanto la sua frase di lancio "Quanto lontano saresti disposto a spingerti per salvare la tua famiglia?" ci fanno pensare che il film sia tratto da una storia vera. E’ così? Non esattamente. La famiglia Dwyer non è mai esistita, ma la sua tumultuosa disavventura sarebbe benissimo potuta accadere al regista John Erick Dowdle mentre era in viaggio in Thailandia insieme a suo padre. Era il 2006 e il paese venne funestato da un colpo di stato, ma l'atmosfera era relativamente tranquilla e i Dowdle fecero i loro giri indisturbati. Tempo dopo, ripensando a quest'esperienza e a cosa sarebbe potuto accadere a uno straniero finito nel bel mezzo di un conflitto armato, il regista ha scritto la sceneggiatura di No Escape. La vera ispirazione del film è stata piuttosto Missing, il film dell'82 interpretato da Jack Lemmon e Sissy Spacek nel quale, nel Cile del 1973, un giornalista scompare in seguito a un golpe.

Le riprese di No Escape, girato nelle città di Chiang Mai e Lampang, non sono state esattamente una passeggiata di salute. L'ultimo giorno Owen Wilson si è lasciato fotografare con dei fan che gli hanno messo intorno al collo un fischietto bianco, rosso e blu. L'attore non lo sapeva, ma quel fischietto lo associava a un gruppo che contrastava il governo. Poco dopo, la produzione del film è stata contattato dall'ufficio del Primo Ministro. "Erano arrabbiati e volevano portarmi in prigione" - ha raccontato Wilson. "Per fortuna ero già ripartito, altrimenti sarebbe stata una bella storia da narrare in un talk show, anche se c'è una bella differenza fra una bella storia e trovarsi in un carcere thailandese".

Prima di questo incidente, c'era stata molta tensione sul set. Proprio mentre Wilson girava una scena in cui si trovava schiacciato tra una folla di manifestanti e dei soldati, alcuni membri della troupe erano appena usciti da una situazione praticamente identica.

Se No Escape ha avuto il via libera dalle sale cinematografiche thailandesi ed è uscito regolarmente al cinema, in Cambogia non ha mai raggiunto gli spettatori. Il Ministero della Cultura, delle Belle Arti e del Cinema, nella persona del direttore Sin Chanchaya, ha detto a un giornalista del Phnom Penh Post che il trailer del film aveva scatenato delle proteste su Facebook perché, nella scena di una rivolta, si vedevano scritte con caratteri Khmer sugli scudi della polizia locale. Le lettere formavano parole insistenti, ma Sin sosteneva che la cosa avrebbe avuto una cattiva influenza sul pubblico cambogiano: "Quelle immagini" - ha spiegato, lapidario - "hanno davvero offeso la nostra cultura".

Nel film di Patricia Riggen, l'attrice è una madre-disastro di un'adolescente ribelle.

Quando Eva Mendes ha interpretato una delle due protagoniste di Girl in Progress aveva già una discreta filmografia alle spalle. Dopo Training Day, in cui era apparsa, anche se per poco, completamente nuda, aveva recitato in Out of Time, Hitch, e soprattutto ne Il cattivo tenente - Ultima chiamata New Orleans e nel bellissimo I padroni della notte di James Gray, con Joaquin Phoenix. In confronto a questi titoloni hollywoodiani, Girl in Progress è un piccolo film indipendente, che però ha il pregio di mescolare attori Usa a talenti dell'America Latina e che esplora in maniera complessa e intelligente un rapporto madre/figlia. La madre, Grace, è un disastro di genitore, perché non c'è mai e, fra lavoro, conti da pagare e un amante sposato, ha troppi pensieri per la testa per comprendere le esigenze dell'adolescente che un tempo era la sua bambina e che si chiama Ansiedad. Quanto all'adolescente, come spesso succede improvvisamente diventa ribelle, un po’ per essere notata e un po’ perché, a quell’età, chi non ne ha combinate di tutti i colori? Girato nel 2012, Girl in Progress è diretto da Patricia Riggen e vede nel cast Cierra Ramirez (Ansiedad), Matthew Modine (nella parte dell'uomo di chi è innamorata Grace) e Patricia Arquette (nel ruolo della professoressa di inglese di Ansiedad).

Girl in Progress è il proseguimento ideale del primo lungometraggio di finzione per il cinema di Patricia Riggen, regista messicana. Se Under the Same Moon ruotava intorno a una madre e un figlio che venivano separati, qui la figlia è diventata figlio. Quanto alla madre, l'attrice che l'avrebbe impersonata doveva essere Eva Mendes fin dal primo istante. Di lei la Riggen ha detto: "Eva ci ha regalato una performance coraggiosa e straordinaria, ha fatto qualcosa che non aveva mai fatto prima, interpretando un personaggio dotato di grande verità. Eva è divertente, commovente e ci mostra un lato di sé che non conoscevamo".

Del personaggio di Grace, Eva Mendes ha amato la cronica disorganizzazione, l’umanità e l’imperfezione. “E’ una sciagurata. Mi piace il fatto che lei stessa sia un work in progress" - ha raccontato, spiegando che anche lei era, ed è, una girl in progress, una persona che, almeno fino al nostro film, ha sempre amato reinventarsi. In che modo? Per esempio facendo corsi di qualunque genere. All'epoca di Girl in Progress, nella fattispecie, la Mendes aveva appena preso un diploma in massaggi, cosa utilissima a lei e alla sua mamma, entrambe tormentate dal mal di schiena.

Interpretare una madre ha aiutato Eva Mendes a strapparsi un po’ di dosso quell'etichetta da bomba sexy che le è stata appiccicata dopo il sopracitato Training Day e dopo I padroni della notte, in cui era davvero hot. "Prima di tutto essere sexy è soltanto una delle mie molte caratteristiche" - ha dichiarato l'attrice in proposito . "Io non sono sexy e basta. Posso esserlo. È un lato di me che posso assecondare così come posso assecondare la mia parte buffa, la mia parte stramba o la mia parte drammatica". E comunque il personaggio che l'attrice interpretava in Training Day era una mamma, e quindi si può essere sia mamme che donne sensuali, come lo sono state Julianne Moore e Annette Bening, i due grandi modelli di riferimento di Eva. La Mendes è entrambe le cose, visto che ha due bambine ed è ancora super sexy.

Eva Mendes adolescente era ribelle esattamente quanto la Ansiedad di Girl in Progress, anche se non aveva una madre così assente. Fino a 13 anni l'attrice era una ragazzina obbediente e diligente, oltre che una studentessa modello. Poi… è scoppiata l’apocalisse. "Penso che il periodo fra la seconda media e il primo o secondo anno di liceo sia stato molto complicato" - ha spiegato Eva - "perché non avevo che una missione. Volevo essere indipendente e libera da ogni condizionamento. Ero molto legata alla mia famiglia e ai suoi valori, ma in quel momento sentivo l'esigenza di 'divorziare' dai miei cari per capire chi fossi veramente. Era quella la mia missione ed era una via molto accidentata da percorrere".

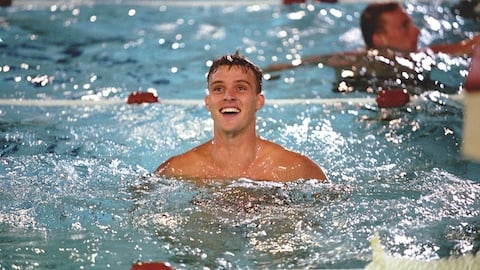

Il film diretto da Russell Mulcahy intitolato Una bracciata per la vittoria è basata su una storia vera, tratta dall'autobiografia dell'ex nuotatore australiano Tony Fingleton.

Se avete letto Open, l'autobiografia dell'ex capione di Tennis André Agassi, avete compreso quanto avere una figura paterna ingombrante possa provocare serie ripercussioni nella vita di uno sportivo. Ci sono tanti modi per stimolare un figlio nella sua attività e non c'è da stupirsi se umiliarlo con un approccio ossessivo abbia in seguito una ricaduta a livello psicologico. Il film Una bracciata per la vittoria è l'adattamento cinematografico di una storia vera, quella dell'australiano Tony Fingleton (interpretato da Jesse Spencer) che lui stesso racconta nell'autobiografia Swimming Upstream (nuotando controcorrente). La figura di suo padre è portata sullo schermo dall'attore premio Oscar Geoffrey Rush, mentre la regia è curata Russell Mulcahy (noto per aver diretto il mitico film Highlander - L'ultimo immortale del 1986).

Anthony J. Fingleton è il vero protagonista di questa vicenda accaduta a cavallo tra gli anni 50 e 60. Cresciuto a Brisbane in Australia, da ragazzo veniva continuamente maltrattato dal violento padre alcolizzato. Per sfuggire ai tesi rapporti in casa, Tony trascorreva diverso tempo insieme a suo fratello John allenandosi nella piscina locale. Il padre, troppo preso dalla carriera pugilistica del primo figlio, non degnava di alcuna attenzione gli altri due, secondo lui più deboli del primogenito. Quando Tony e John dimostrarono di avere un grande talento nel nuoto, attirarono l'interesse del padre che iniziò a vessarli con duri allenamenti. Soltanto John ottenne la stima del genitore, mentre Tony continuava a essere sminuito, fino a quella gara per i Giochi del Commonwealth nel 1962 in cui vinse la medaglia d'argento per poi decidere in seguito di emigrare da solo negli Stati Uniti grazie a una borsa di studio a Harvard. Oggi è sceneggiatore e produttore di film e opere teatrali.

Nel video qui sotto la vera finale dei 200 metri dorso dei Giochi del Commonwealth del 1962 che si sono svolti a Perth, in Australia, con l'arrivo al secondo posto di Tony Fingleton.

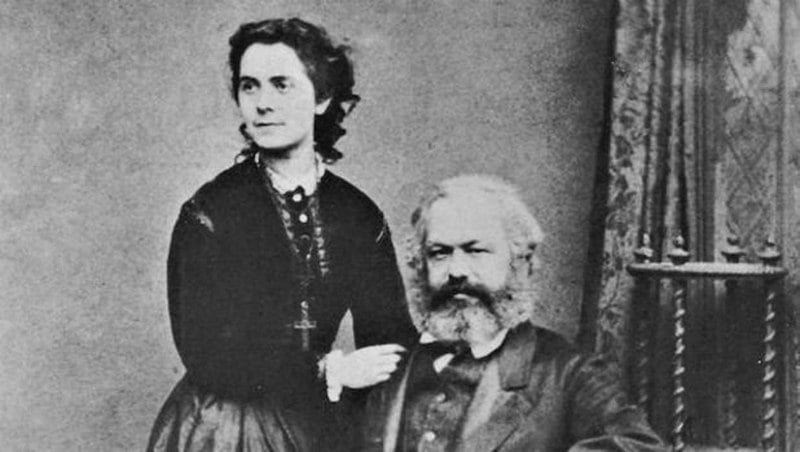

Diretto da Raoul Peck, il film è incentrato sul dibattito politico che portò alla creazione del Manifesto del partito comunista di Marx ed Engels, ma raccontando un'epoca parla anche di oggi.

Se amate la storia e siete curiosi di conoscere l'origine dei movimenti che hanno cambiato il mondo, senza fermarvi alla superficialità delle ideologie, le cui parole vengono oggi usate spesso senza alcuna conoscenza oggettiva dei fatti, avrete visto o dovete assolutamente vedere Il giovane Karl Marx, il film del 2017 del regista haitiano Raoul Peck, interpretato da due attori tedeschi: August Diehl nel ruolo del titolo e Stefan Konarske in quello di Fredrich Engels. Nel cast ci sono anche Vicky Krieps, l'attrice lussemburghese rivelata in tutto il suo talento da Il filo nascosto di Paul Thomas Anderson, nella parte della moglie di Marx, Jenny Von Westphalen, e nel ruolo degli anarchici Pierre Proudhon e Mikhail Bakunin, il belga Olivier Gourmet e il ceco Ivan Franek, che ha lavorato spesso anche nel cinema italiano. Il giovane Karl Marx racconta l'incontro e l'amicizia tra Marx ed Engels, che li portò alla stesura congiunta del Manifesto del partito Comunista nel 1848.

Siamo abituati a identificare Karl Marx nelle foto che lo ritraggono con una folta barba bianca ma, come dice la frase di lancio del film, “La rivoluzione è giovane” e all'epoca in cui si svolgono i fatti raccontati nella storia (il suo secondo incontro con Engels, nel 1844), il filosofo creatore delle basi ideologiche del comunismo aveva 26 anni. August Diehl, che lo interpreta, è un po' più grande: ne aveva 41 quando è uscito il film. Il pubblico italiano conosce sicuramente l'attore per le sue partecipazioni a Il falsario, Bastardi senza gloria (dove era il maggiore della Gestapo Hellstrom), Salt e La vita nascosta. Tornando a Karl Marx, all'epoca dell'incontro con Engels viveva a Parigi, dove scriveva su vari giornali radicali e da dove venne espulso nel 1849, per le sue idee e in seguito ai moti popolari che a queste si ispirarono. Da lì si trasferì con la moglie e i figli a Bruxelles e in seguito a Londra, dove continuò a lavorare come giornalista prima di iniziare il suo magnum opus: la stesura de "Il Capitale", di cui riuscì a pubblicare solo il primo volume nel 1867. Il compito di pubblicare postumi altri due volumi dell'opera venne assunto proprio da Engels che li dette alle stampe nel 1885 e nel 1894. Karl Marx, le cui teorie economiche e sociali rivoluzionarono il diciannovesimo secolo, morì a Londra il 14 marzo del 1883 all'età di 65 anni, non riuscendo a riprendersi dalla morte dell'amatissima Jenny, scomparsa due anni prima, e della primogenita che portava il nome della madre.

Un destino terribile sembra perseguitare la famiglia Marx: le altre due figlie del filosofo, donne intellettuali e impegnate, Laura ed Eleanor, muoiono entrambe suicide, la prima assieme al marito socialista Paul Lafargue (sono sepolti al Pére Lachaise di Parigi) e la seconda, Eleanor Marx detta Tully, a 43 anni, dopo aver scoperto le nozze segrete del suo compagno, il politico Edward Aveling, rimasto vedovo. Durante la sua vita Karl Marx, questo grande pensatore autore di una quantità impressionante di articoli, saggi, volumi di politica economica e filosofia, si trovò spesso in condizioni al limite della sopravvivenza e venne sempre supportato dall'amico Friedrich Engels, che pronunciò anche la sua orazione funebre.

L'amico di una vita e collaboratore di Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, è interpretato da Stefan Konarske, anch'egli più grande (di 13 anni) del personaggio che interpreta, che aveva all'incirca 24 anni all'epoca degli eventi raccontati nel film. Mentre l'amico proveniva da una famiglia della media borghesia, Engels era figlio del proprietario di filande di cotone e importanti fabbriche tessili in Inghilterra e Prussia, e questo gli diede modo di toccare con mano la condizione dei lavoratori salariati. Intelligente e sensibile, nel 1839, quando non ha ancora 19 anni, pubblica sotto pseudonimo un articolo proprio su questo argomento. Non è ateo come Marx, ma, pur distanziandosi dalla religione pietista del padre (che non gli impedisce di sfruttare i suoi lavoratori, bambini inclusi), ha come riferimento i Vangeli prima, e poi la filosofia di Hegel. Determinante per lui, dopo i disaccordi iniziali sorti tra di loro, è il secondo incontro con Marx, avvenuto a Parigi nel 1844, e la conoscenza della condizione della classe operaia inglese durante la rivoluzione industriale, su cui scrive un importante saggio. Nel 1847 il congresso della neonata Lega Comunista affida a lui e a Karl Marx il compito di stilare quello che diventerà il Manifesto del partito comunista, che si apre con le celebri parole “Uno spettro s'aggira per l'Europa - lo spettro del comunismo”. Anche Engels lascia alla sua morte, avvenuta nel 1895 all'età di 75 anni, molti scritti di politica, economia politica e filosofia. A Berlino una scultura celebra i due grandi filosofi: Marx seduto ed Engels in piedi.

Jenny Von Westphalen, interpretata nel film da Vicky Krieps, è stata l'amatissima moglie di Karl Marx, la donna che gli ha dato in tutto sette figli (quattro dei quali morti da piccoli) e ne ha condiviso le lotte e la miseria, fino alla morte, avvenuta nel 1881 all'età di 67 anni. Ne ha 29, 4 più del marito, quando unisce la sua vita a quella di lui. È la figlia di un barone tedesco, amico del padre di Marx, ed è bella, bionda e intelligente. I due si conoscono fin da bambini, si frequentano da adolescenti e si innamorano, fidanzandosi nel 1836 e sposandosi nel 1843. Jenny, critico teatrale e attivista politica, sarà l'unica donna della vita del filosofo. Questa la descrizione del loro rapporto da parte del socialista tedesco Stephan Born: “Marx amava la moglie, ed ella condivideva il suo amore. Ho conosciuto raramente unioni altrettanto felici, in cui la gioia, la sofferenza (che non fu loro risparmiata) e il dolore fossero condivisi con una tale certezza di reciproco possesso. Ed ho raramente incontrato una donna che fosse più armoniosa della signora Marx sia nel fisico sia per le qualità della mente e del cuore, e che, sin da un primo incontro, facesse una così favorevole impressione. Era bionda; i suoi figli, allora ancora piccoli, avevano i capelli e gli occhi neri come il padre”.

Il compito di raccontare un'amicizia e un periodo storico tanto importanti per il futuro del mondo è stato assunto dal regista haitiano e attivista politico Raoul Peck, che ad Haiti è stato per diversi anni anche ministro della cultura. Prima di diventare regista, Peck ha passato un anno come tassista a New York, e ha fatto il fotografo e il giornalista, prima di laurearsi alla German Film and Television Academy di Berlino Ovest nel 1988. Dopo una serie di cortometraggi documentari dirige nel 2000 Lumumba, un film biografico sul leader del Congo indipendente. Nel 2017 il suo documentario I'm Not Your Negro, sulla storia del conflitto razziale in America, partendo dalle parole di un libro incompleto dello scrittore di colore James Baldwin, viene candidato all'Oscar.

Detroit, con John Boyega, Will Poulter e Anthony Mackie, è un durissimo film che racconta una specifica vicenda all’interno dei moti razziali nella città americana.

Una delle autrici più importanti del cinema americano di oggi, anche se decisamente poco prolifica. Kathryn Bigelow ha raccontato le pieghe nascoste e le ferite più vive della società americana in guerra nello splendido Zero Dark Thirty o in The Hurt Locker, ma anche quella del fronte interno in Detroit. Un fronte apparentemente lontano, ma che nel suo film, drammaticamente sottovalutato, ha dimostrato come sia ancora profondamente vivo nell'America di oggi. Stiamo parlando della questione della razza, della diseguaglianza sociale di cui sono vittime le minoranze.

Complesso nella gestazione, Detroit è stato accolto molto più freddamente degli altri film della Bigelow, vista l'ambientazione diversa dalle sabbie del medio oriente e prossima invece alle strade insanguinate dell'America degli anni 60, in preda alle reazioni razziste alle sacrosante lotte per i diritti umani degli afroamericani.

Terza collaborazione con lo scrittore e sceneggiatore Mark Boal, ci porta ai giorni dal 23 al 27 luglio 1967, a Detroit, Michigan, dove scoppiarono degli scontri in seguito all'irruzione della polizia in un bar privo della necessaria licenza. Un tributo di sangue pesantissimo fu la conseguenza di quei giorni sciagurati, con ben 43 morti, 1190 feriti e oltre 7000 arresti. Non solo, furono danneggiati fortemente o distrutti addirittura 2000 edifici.

La Bigelow si concentra in particolare su uno degli avvenimenti, accaduto all'Algiers Motel, per il quale furono processati tre poliziotti, con l'accusa di aver ucciso a sangue freddo, senza motivazioni, tre giovani afroamericani. Una storia assurda e complessa, proposta con concitazione da una regia che non lascia un attimo di tregua e cerca di riproporre la contrazione di quelle ore, utilizzando per questo attori non molto noti, come John Boyega, Will Poulter, Algee Smith, Jacob Latimore.

Il film, dal budget di 34 milioni di dollari, uscì nelle sale americane esattamente a 50 anni di distanza dai fatti, il 26 luglio del 2017, incassando però solo 26 milioni. La Bigelow, in passato sposata con James Cameron dal 1989 al 1991, ha diretto in carriera solo dieci film, dal 1982 al 2017, finendo per vincere, prima donna in assoluto, l'Oscar per la miglior regia nel 2010 per The Hurt Locker. Sono state quattordici le nomination agli Academy Award ottenute dai suoi film.

La rivolta della 12° strada. È così che sono passati alla storia americani i giorni di vera sommossa della popolazione nera contro la polizia nel corso del luglio 1967. Come detto, l’evento che scatenò il tutto fu l'irruzione della polizia nel Blind Pig, bar notturno senza licenza, posto proprio in quella che all’epoca era la 12th street e ora si chiama, significativamente, Rosa Parks Boulevard, dal nome dell’attivista che, rifiutandosi di cedere il suo posto a un bianco, nel 1955, a Montgomery, Alabama, scatenò la prima miccia della lotta per i movimenti civili. La Parks visse proprio a Detroit dagli anni 60 fino alla morte, nel 2005.

Lo scontro fra polizia e passanti deflagrò poi in una delle più violente rivolte della storia degli Stati Uniti. Per riportare la quesite fu necessario l’intervento della Guardia Nazionale del Michigan, ordinata dal governatore dello stato, mentre il presidente Johnson mandò due divisioni dell’esercito.

Il regista David Barrett racconta come ha girato Fire With Fire con Bruce Willis, Rosario Dawson e Josh Duhamel.

Fire With Fire con Josh Duhamel, Bruce Willis, Rosario Dawson e Vincent D'Onofrio non è, come potreste pensare guardando i nomi coinvolti, una grande produzione: diretto dallo stuntman e regista televisivo David Barrett, è una coproduzione disperata indipendente portata a termine da sette piccole compagnie diverse. Per qualcuno i 21 executive producers sul progetto sono un record. Uscito negli States direttamente in homevideo, ha visto un veloce passaggio in sala in Italia, e ha una fama tremenda. Più che invitarvi a rivalutare il film, vogliamo spingervi a capire come possa essere portato a termine un progetto di questo tipo. Diamo quindi voce proprio al regista David Barrett, combinando stralci di interviste a Hollywood News, Geek Syndicate e The Fan Carpet.

Tra tv e cinema, David Barrett non sarà noto ai cinefili, ma ha un curriculum colossale tra televisione e cinema: non è una di quelle carriere che attirano l'attenzione, ma è più che sufficiente a ottenere miracoli, come coinvolgere il notoriamente esoso Bruce Willis in un progetto indipendente a basso budget... C'è del ragionevole orgoglio nel tono di Barrett.

Ho fatto un sacco di lavoro nelle seconde unità, per esempio le sequenze d'azione di Final Destination 2 sono state citate da Steven Spielberg e Peter Jackson, poi ho diretto seconde unità in film come Orphan e Stigmata che ho anche prodotto. E' dura ottenere l'opportunità di fare un lungometraggio perché io sono sempre stato "quello della seconda unità" o il "tizio della tv". Ho pensato di poter trasformare il copione in qualcosa di speciale, di prendere un attore come Josh Duhamel e portarlo dove non era mai andato prima, volevo provare di poter lavorare con gli attori. [...]

Avevo fatto prima film con Bruce Willis come stuntman, quando feci Impatto imminente, l'avevo incontrato un paio di volte. Mio padre era la controfigura di Burt Reynolds e Paul Newman, Paul era il mio padrino, in una delle sue corse d'auto ci capitò d'incontrare Bruce, l'avevo visto altre volte. Naturalmente lui non si ricordava, ma quando ha accettato ho capito di avere il film, ero al settimo cielo. Non è tanto presente nel film, ma manda avanti la storia.

Fire With Fire è stato giustamente criticato per un allestimento che non rende giustizia al film d'azione che dovrebbe essere. Non pensate per un attimo che David Barrett non ne fosse consapevole...

Sapevo di avere 45 giorni per girare il film, sapevo che nel mondo della tv non c'è nessuno che gira veloce come me, tante serie che ho fatto hanno avuto nomination per l'azione, per gli Emmy, quindi so essere estremamente efficiente, però... all'improvviso la produzione mi disse che dovevo preparare il film in poche settimane e girare in 20 giorni. Mi sono trovato in una situazione in cui era impossibile ottenere quello che ci si aspettava da me. A quel punto ho dovuto fare un film al meglio delle mie capacità, con il tempo e le risorse che avevo. La cosa triste è che questo film poteva essere davvero spettacolare se avessimo avuto il tempo necessario, ma con 20 giorni non so se saremmo mai riusciti a farlo meglio di com'è venuto.

Barrett spiega poi nel concreto, con un esempio, quanto la produzione di Fire With Fire sia stata folle.

Quando vi dico che faccio episodi di serie tv che costano più di Fire With Fire, non sto dicendo una bugia, abbiamo fatto questo film per la metà del budget che usiamo per puntate di serie tv in cui lavoro. Per darvi un esempio migliore, Once Upon a Time è un'altra serie in cui giri un episodio di 44 pagine in 9-10 giorni. Noi avevamo un copione di 106, nessun set costruito appositamente, una troupe che non si conosceva, nessun budget: girare una cosa del genere in venti giorni è follia. [...]

Siccome conosco le scene d'azione e ho pratica di produzione sono stato in grado di farlo. L'ho impostato in modo da poter raccontare la storia in modo molto veloce. Ho girato l'azione come se fosse un lavoro teatrale, girando dall'inizio alla fine della scena, senza staccare mai. Se funziona in un take solo, ripreso da diverse angolazioni e camere, allora ottieni qualcosa di realistico.

In onda oggi pomeriggio sui canali TV in chiaro: Una oscura sparizione, La maledizione del re nero, Un marito da addestrare, Prova a prendermi, Partnerperfetto.com e tanti altri.

Ricordiamo che in questo periodo di Emergenza Coronavirus, i palinsesti di tutti i canali TV sono suscettibili di modifiche dell'ultimo minuto.

Film oggi pomeriggio in TV. Tra quelli in onda oggi sui canali TV in chiaro: Una oscura sparizione, La maledizione del re nero, Un marito da addestrare, Prova a prendermi, Partnerperfetto.com e tanti altri.

(Thriller, Canada 2019, durata: 90 min), in onda alle 14:30 su Tv8.

Un film di Max McGuire con Michelle Mylett, Jacob Blair, Anna Hardwick, Scott Gibson, Allison Graham, Kyle Buchanan, Paolo Mancini e Richard Chuang.

Trama del Film Una oscura sparizione: il film è la storia di una giovane ragazza vittima di rapimento. Dopo essere stata sequestrata, torturata e abusata, Elle Whitland (Michelle Mylett) viene rilasciata fuori da una stazione di servizio senza alcuna motivazione apparente. Dopo essersi riunita con il fidanzato Billy (Jacob Blair) e sua sorella Jen (Anna Hardwick), i tre vengono condotti alla stazione di polizia per affrontare un lungo interrogatorio. Ma la vicenda della cattura non è chiara e le versioni dei tre sembrano fare acqua da tutte le parti.

(Fantasy, Avventura, Germania 2017, durata: 99 min), in onda alle 15.55 su Italia 1.

Un film di Christian Theede con Danylo Kamenskyi, Oleksandr Komarov, Roman Lutskyi, Oleh Voloschenko, Georgiy Derevyanskiy, Ivan Denysenko, Eva Koshova, Stanislava Krasovskaya, Natalya Sumskaya e Erbolat Toguzakov.

Trama del Film La maledizione del re nero: vede protagonisti due ragazzini intraprendenti alle prese con un intricato enigma da risolvere. Mia (Marleen Quentin), dodici anni, e il suo compagno di classe Benny (Ruben Storck), sono "i Grani di Pepe di Amburgo", due investigatori in erba che adorano fare indagini. In vista della prossima gita scolastica, i piccoli lasciano la città e raggiungono il ranch della famiglia Gruber, tra le montagne dell'Alto Adige. Ma la pace e la serenità di quel luogo idilliaco durano ben poco. Presto, infatti, Mia, Benny e il loro amico Luca (Leo Gapp), vengono scossi da una serie di eventi misteriosi. Per Luca non c'è dubbio, la fattoria è stata colpita dall'antica maledizione del Re Nero.

(Commedia, USA 2018, durata: 85 min), in onda alle 16:10 su Iris.

Un film di Sandra L. Martin con Julie Gonzalo, Jonathan Chase, Luciana Faulhaber, Karla Mosley, Jordan Monaghan, Andre Hall, Kayla Harrity e Matt Walton.

Trama del Film Un marito da addestrare: il film è la storia di una psicoanalista alle prese con i problemi relativi al suo matrimonio. Jillian James(Julie Gonzalo), è una terapista matrimoniale di successo e autrice di noti best seller, molto abile nell'aiutare e sostenere le persone che si trovano ad affrontare difficoltà matrimoniali, ma non altrettanto brava con la sua vita privata. Infatti, nonostante la carriera lavorativa di Jillian prosegua a gonfie vele, la sua relazione coniugale sembra andare in mille pezzi, ma la donna per paura di essere giudicata dagli altri non vuole ammetterlo e finge che tutto stia andando bene. Fino a quando suo marito Justin (Jonathan Chase) non la costringe a confrontarsi con la realtà e i loro problemi.

(Commedia, Biografico, USA 2002, durata: 141 min), in onda alle 16:40 su Iris.

Un film di Steven Spielberg con Leonardo DiCaprio, Tom Hanks, Christopher Walken, Martin Sheen, Nathalie Baye, Amy Adams, James Brolin, Frank John Hughes, Brian Howe, Steve Eastin, Chris Ellis, Jennifer Garner, Nancy Lenehan, Ellen Pompeo, Elizabeth Banks, Candice Azzara e Kaitlin Doubleday.

Trama del Film Prova a prendermi: protagonista della vicenda è il sedicenne Frank Jr Abagnale (Leonardo DiCaprio) che, nella New York degli anni Sessanta, è posto davanti al più terribile dei dilemmi: scegliere con quale genitore vivere a seguito di un burrascoso divorzio. Piuttosto che far soffrire il padre Frank (Christopher Walken) e la madre Paula (Nathalie Baye), il ragazzo preferisce fuggire. È così che Frank svilupperà il suo magistrale talento per la truffa. Quando i pochi soldi a sua disposizione finiscono, il giovane cambia il suo cognome in Taylor, tentando di persuadere varie banche a fornirgli un nuovo blocchetto di assegni. La prima truffa, tuttavia, fallisce e Frank decide di tentare un’impresa più adrenalinica. Il ragazzo, infatti, raccoglie tutte le informazioni necessarie per spacciarsi per un pilota della Pan Am. Frank fabbrica abilmente le prove della sua assunzione e si procura la divisa della compagnia aerea. I suoi illeciti attirano l’attenzione dell’agente dell’FBI Carl Hanratty (Tom Hanks), che promette di dargli la caccia. Grazie alla sua astuzia, Frank semina l’agente e si trasferisce in Georgia, cambiando la sua identità in Frank Conners. Dopo essersi invaghito dell’infermiera Brenda Strong (Amy Adams), Abagnale falsifica una laurea in pediatria ad Harvard per esercitare come medico nello stesso ospedale della ragazza. Hanratty, intanto, continua ad indagare.

(Commedia, Sentimentale, USA 2005, durata: 98 min), in onda alle 17:55 su La5.

Un film di Gary David Goldberg con Diane Lane, John Cusack, Elizabeth Perkins, Dermot Mulroney, Christopher Plummer e Stockard Channing.

Trama del Film Partnerperfetto.com: Sarah Noland (Diane Lane), un'insegnante di scuola materna, è una quarantenne ancora ferita dal suo divorzio. Non ha la minima intenzione di cercare un altro partner, ma la sua famiglia ha altri programmi per lei. E così le sue sorelle Carol (Elizabeth Perkins) e Christine (Ali Hillis) la iscrivono su PerfectMatch.com, un sito di incontri on line, specificando che il partner perfetto deve amare i cani, perché chi ama i cani non può essere una persona cattiva. Sarah alla fine si arrende e accetta di incontrare alcuni pretendenti. Nel frattempo, anche Bill (Christopher Plummer), il padre vedovo di Sarah, decide di cimentarsi con gli appuntamenti on line e inizia una relazione con Dolly (Stockard Channing). Dopo una serie di appuntamenti disastrosi, Sarah incontra Jake Anderson (John Cusack), un costruttore di barche in legno, un uomo romantico e idealista con le sue stesse cicatrici da divorzio.

Tutti i Film e i Programmi Stasera in TV

Prosegue la nostra rubrica per orientarsi nel palinsesto televisivo. Nel menù di giovedì 30 le notti di Pasolini e Sutton, Garrone prima maniera, un grande thriller politico di Costa-Gavras e la premiata coppia Totò-De Sica.

Prosegue la rubrica che ogni giovedì propone piccole perle di cinema conservate nei nostri archivi. In questo ottavo appuntamento la gioia di ritrovarsi e della condivisione in due vedute di inizio '900 di Luca Comerio e Giovanni Vitrotti.

Josh Cooley, che ha diretto il premio Oscar Toy Story 4, dirigerà un prequel animato per il cinema di Transformers.

La divisione cinematografica della Hasbro (eOne) e la Paramount hanno scritturato il regista Josh Cooley - che ha diretto il film animato premio Oscar Toy Story 4, per affidargli quello che viene presentato come un prequel di animazione per il cinema di Transformers.

Si tratta a quanto riporta Deadline Hollywood di un progetto ambizioso che si svolgerà su Cybertron, il pianeta da cui hanno avuto origine i robot buoni e cattivi. Il film si incentrerà sul rapporto tra Optimus Prime e Megatron. Esiste già una sceneggiatura, scritta da Andrew Barrer e Gabriel Ferrari, che hanno lavorato al primo Ant-Man e sono gli sceneggiatori del sequel Ant-Man and the Wasp.

Il film animato dei Transformers è separato da quelli in live action e dallo spin-off Bumblebee, che vanno avanti indipendentemente da questo. Probabilmente il necessario distanziamento sociale di questo periodo favorirà i progetti di animazione, visto che buona parte del lavoro in questi casi può essere fatto in regime di isolamento.

Al momento Cooley sta rivendendo l'ultima versione della sceneggiatura assieme agli autori, che lavorano da anni a un progetto che è da tempo in preparazione, e che ha ricevuto adesso una significativa accelerazione dopo che è stato scritturato il regista.

Ideata e scritta da Ettore Belmondo, The Zoomroom è la prima web-serie realizzata ai tempi del Coronavirus.

Il mondo dell'intrattenimento è quello che per primo ha risentito della quarantena forzata: teatri chiusi, set cinematografici e televisivi bloccati e tutte le maestranze a casa; in tutti i sensi. E ancora oggi non si sa quale sia il destino degli artisti. Quando e come si potrà tornare a fare teatro, cinema e televisione?

The Zoomroom è il tentativo di smart-working laddove sembrava impossibile.

Come sarebbe stata in Titanic la famosissima scena “Jack, sto volando”, se Jack e Rose avessero mantenuto fra loro un metro di distanza? Oppure, come sarebbe stata quella del vaso di Ghost – Fantasma in video chat? Come si fa a fare cinema o televisione in queste condizioni?

Il giorno successivo al decreto con cui il Presidente del Consiglio Giuseppe Conte dichiara l'intero territorio italiano zona protetta , la società che possiede il portale online generalista “Butterfly Effects” si trova in crisi: non solo salta il progetto del film Cuore di farfalla, a cui

stava lavorando, ma il portale stesso rischia di chiudere. La vicenda segue le relazioni, le preoccupazioni, le discussioni e i progetti di quattordici personaggi coinvolti a vario titolo nelle vicende imprenditoriali di “Butterfly Effects” e che si trovano ad affrontare una crisi alla quale erano totalmente impreparati.

Lo stesso Belmondo – che a Ottobre, inoltre, vedremo su Rai Uno nella serie tv Io ti cercherò con Alessandro Gassman – partecipa anche in qualità di attore ai dieci episodi, della durata oscillante tra i dodici e i quindici minuti ciascuno e rilasciati, di settimana in settimana, il Venerdì su YouTube e Facebook ai seguenti indirizzi:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCD...

https://www.facebook.com/TheZoomRoo...).

The Zoomroom è una produzione collettiva e a budget pressoché pari a zero realizzata da The ZR Woo-Hoo Company.

Tutti gli episodi vengono girati direttamente online, in video chat, sfruttando gli strumenti forniti da Zoom, salvo alcuni casi in cui sono gli attori stessi a girare qualche inquadratura utilizzando il proprio smartphone. Il calendario settimanale è strutturato come una vera e propria produzione: la sceneggiatura di ogni episodio viene distribuita entro la Domenica sera; il Lunedì si tiene una riunione pre-produzione; il Martedì e il Mercoledì si registrano le scene; il Giovedì e parte del Venerdì si monta il materiale (effetti, musiche).

Oltre a Belmondo, costituiscono il cast di The Zoomroom Mario Battisti, Agnese Brighittini (Caro Lucio ti scrivo di Riccardo Marchesini), Federica Cignotti, Stefano D'Ottavio, Tiziano Ferracci (Domina di Claire McCarthy), Lorella Lombardo, Luigi Martini, Livia Massimi, Alberto Mazzaro, Francesca Nobili (la Flora Del Colle di Un posto al sole), Francesco Petit-Bon, Franco Petit-Bon e Francesca Stagnì.

Trailer: https://youtu.be/_E5RlHuqc5U

In questo difficile momento la onlus di cui Anna Foglietta è presidente unisce le forze con Banco Alimentare per aiutare a sfamare i minori in difficoltà, particolarmente colpiti dall'emergenza coronavirus.

Diamo volentieri la notizia di questa iniziativa della onlus Every Child Is My Child, presieduta da Anna Foglietta, che non è solo una bravissima attrice ma anche un'attivista e una donna impegnata nel sociale. L'associazione riunisce molti esponenti del mondo dello spettacolo italiano e ha unito le forze con Banco Alimentare per aiutare i minori in difficoltà in questo drammatico momento:

La Onlus “Every Child Is My Child” supporta l’operato della rete Banco Alimentare nell’emergenza Covid-19 affinché nessun bambino soffra la fame. Every Child is My Child di cui Anna Foglietta è presidente, è la prima organizzazione composta da tante persone dello spettacolo che tutte assieme si sono spese per sensibilizzare l’opinione pubblica dicendo “Basta” alla guerra in Siria.

ECIMC è così divenuta da movimento ad associazione concreta a sostegno di organizzazioni nazionali, europee e internazionali a difesa dei diritti civili dei bambini. “Ogni bambino è il nostro bambino”: è questo il fondamento della Onlus che decide di fare qualcosa anche per i nostri bambini che, oggi più che mai, stanno soffrendo la fame. In questo momento storico così difficile, in cui le richieste di aiuto alimentare stanno progressivamente aumentando, Every Child is My Child e Banco Alimentare promuovono una raccolta fondi il cui ricavato verrà convertito in alimenti che grazie all’impegno di Banco Alimentare arriveranno sulle tavole di tante famiglie bisognose.

Tra coloro che hanno aderito alla campagna, oltre ad Anna Foglietta, Vittoria Puccini, Paola Minaccioni, Edoardo Leo, Andrea Bosca, Donatella Finocchiaro, ci sono: Antonio Cabrini, Emma Marrone, Fiorella Mannoia, Lino Guanciale, Marco D’Amore, Maria Pia Calzone, Martina Colombari, Paola Cortellesi, Sarah Felberbaum e molti altri si stanno mostrando interessati.

“Siamo molto preoccupati perché c’è un’emergenza sociale che si somma a quella sanitaria, – afferma Giovanni Bruno, Presidente della Fondazione Banco Alimentare Onlus – . In questo momento siamo impegnati a sostenere più di 350.000 minori in Italia attraverso le oltre 7.500 strutture caritative territoriali convenzionate. Per questo siamo grati a Every Child is My Child che è riuscita a mobilitare il mondo dello spettacolo; è davvero importante in questo momento il coinvolgimento di tutti. Solo insieme possiamo farcela.”

Banco Alimentare, attraverso la rete di 21 Organizzazioni diffuse su tutto il territorio nazionale, promuove il recupero delle eccedenze alimentari e la loro redistribuzione a 7.500 strutture caritative che assistono 1.500.000 persone bisognose. Gli alimenti salvati dallo spreco riacquistano valore e diventano ricchezza per chi ha ancora troppo poco e spesso ci vive accanto. Per saperne di più e sostenere l’iniziativa https://ift.tt/2xka55J

Il film di Gus Van Sant che ha rivelato al mondo il talento di Matt Damon e Ben Affleck. Appuntamento su SimulWatch giovedì 30 aprile alle 14.

La visione condivisa di giovedì 30 aprile organizzata dalla redazione di Comingsoon.it su SimulWatch, la nostra app disponibile gratuitamente su Google Play e App Store, è quella di uno dei film più celebri degli anni Novanta, amatissimo tanto dal pubblico quanto dalla critica Will Hunting - Genio Ribelle.

L'appuntamento per vedere tutti insieme Will Hunting - Genio Ribelle e commentarlo con amici e familiari, ognuno a casa propria, attraverso la chat di SimulWatch è fissato per giovedì 30 aprile alle ore 14.

Diretto da un Gus Van Sant tutto al servizio della storia che racconta, trattenendo le sue corde più astratte e sperimentali, Will Hunting - Genio Ribelle è il film che ha rivelato al mondo il talento di Matt Damon e Ben Affleck: che qui non sono solo interpreti (Damon nei panni del protagonista, affiancato da Robin Williams premiato con l'Oscar per la sua interpretazione; Affleck in quelli di un suo amico), ma anche autori della sceneggiatura, che gli è valsa un premio Oscar.

La storia è quello di un ragazzo geniale ma problematico di Boston, che per tirare a campare fa le pulizie presso il prestigiosissimo Massachussets Institute of Technology. Lì, risolvendo un difficile problema rimasto su una lavagna, si accorgono delle sue prodigiose doti matematiche, e per aiutarlo a tenere a bada il suo carattere violento e gli istinti autodistruttivi, lo faranno seguire da uno psicologo che aiuterà Will a incanalare la sua rabbia in modo costruttivo.

SimulWatch è la app creata da Coming Soon che è sia motore di ricerca di film all'interno di tutte le piattaforme di streaming legale operanti in Italia, sia una piattaforma attraverso la quale fissare appuntamenti condivisi per la visione di un film e commentarlo attraverso la chat interna con amici, parenti o perfino sconosciuti comodamente dal divano di casa vostra.

Il prossimo appuntamento con la visione condivisa SimulWatch sarà con: Zombeavers.

Non si terrà il Locarno Film Festival 2020, che verrà sostituito da una serie di proposte a sostegno delle produzioni indie in grande difficoltà.

Non si ferma purtroppo la serie di cancellazioni nel calendario estivo dei grandi festival internazionali. Oggi è toccato al Locarno Film Festival annullare la sua 73° edizione, prevista in principio nella prima metà di agosto 2020.

Constatata l’inattuabilità della manifestazione nella sua regolare forma fisica a causa dell’emergenza sanitaria e delle odierne direttive delle autorità federali riguardanti i grandi eventi, il Consiglio direttivo e il Consiglio di amministrazione del Locarno Film Festival, sotto la presidenza di Marco Solari, annunciano che, non essendo possibile un’edizione incentrata sull’incontro e la condivisione degli spazi fisici, il Festival cambia forma e rilancia con Locarno 2020 – For the Future of Films, un’iniziativa volta al sostegno del cinema d’autore indipendente.

Con rammarico il Consiglio direttivo del Locarno Film Festival annuncia l’annullamento di Locarno73. Costretta quindi a rinunciare alla consueta selezione di lungometraggi in prima visione e di principio ai luoghi fisici di incontro, a partire dall’iconica Piazza Grande, la manifestazione ha deciso di proporre un’alternativa all’idea classica di festival cinematografico con cui sostenere nella misura possibile, grazie ai suoi partner, l’industria cinematografica internazionale e svizzera, che sta affrontando una profonda crisi. Locarno 2020 – For the Future of Films, con una serie di progetti mirati, fornirà un supporto al cinema d’autore indipendente e alle sale cinematografiche, e proporrà al pubblico e ai professionisti dell’industria contenuti speciali su diverse piattaforme tra cui, qualora gli scenari in continua evoluzione lo permettessero, proiezioni fisiche in totale sicurezza.

Locarno 2020 è pensata per intervenire sull’immobilismo forzato dell’industria cinematografica, interagendo con gli autori che hanno dovuto interrompere la lavorazione delle proprie opere, assegnando dei Pardi speciali e altri premi alle produzioni cinematografiche internazionali e svizzere ferme a causa dell’emergenza sanitaria globale.

Il Presidente del Locarno Film Festival, Marco Solari: “La decisione odierna del Consiglio federale non ci coglie impreparati. In queste ultime settimane la Direzione artistica e la Direzione operativa, in stretta collaborazione con il Consiglio direttivo, hanno elaborato vari scenari in parte forzatamente abbandonati nel tempo. Nella sua ultima seduta il Consiglio di Amministrazione del Festival, tenendo conto dei rischi sanitari anche per incontri tra meno di mille persone e non potendo preservare lo spirito di Locarno con soluzioni a prima vista anche accattivanti, ha deciso all’unanimità di rinunciare di principio alla manifestazione fisica. il Festival vuole confermare la sua presenza al fianco del pubblico e dell’industria cinematografica con un progetto atto a tradurre in una nuova forma, su altri palcoscenici e piattaforme, i valori che hanno caratterizzato la sua decennale storia.”

La Direttrice artistica Lili Hinstin: “Il Festival deve anzitutto servire i film, e organizzare delle première online nel mese di agosto non ci sembra il modo migliore per farlo. Il nostro ruolo è quello di fare da trait d’union fra i film, l’industria e il pubblico, e abbiamo quindi cercato proposte alternative per svolgere questa nostra missione, verificando dove il nostro intervento potesse rivelarsi più utile in questo momento. Siamo al lavoro per concepire un progetto coerente, in linea con la storia del Festival, all’insegna della solidarietà, e che possa giovare al nostro pubblico e ai registi in difficoltà.”

Locarno 2020 – For the Future of Films , declinata in ogni suo progetto e iniziativa, sarà presentata al pubblico e alla stampa nelle prossime settimane.

Summer at Grandpa’s (Hou, 1984).

DB here:

This is another phantom entry I posted as Private for the seminar I’ve been teaching this term. I’ve opened it up for a wider audience because some readers have written to ask for access to the ideas. These are comments based on assigned reading for the course. Just as important, this entry serves as an introduction to a guest post coming up next week from Malcolm Turvey.

An earlier phantom entry, which considers how critics interpret a movie’s themes, intersects with this one. This is no less wonkish than that was.

The course has been an examination of the theory and practice of a particular perspective on studying film, the poetics of cinema. A poetics of any medium tries to study the principles undergirding the craft (technê) of artistic work in that medium. These principles may be explicit rules, or guidelines steering the makers’ decisions. But poetics can also reasonably try to trace how those principles and practices are designed to shape effects on perceivers. (For film, let’s call them spectators, but they of course listen as well as watch.) What are some fruitful ways to think about effects?

My initial stab at this was the bottom-up/top-down diagram of viewer activity.

To recap: As viewers we have capacities that are data-driven (bottom-up); these yield what we normally call perception. That’s already a huge range of activities, carried out mostly below the level of consciousness. (You can’t watch yourself registering color wavelengths.) In film viewing, perception runs from very fast, encapsulated, specialized, and “dumb” systems, like the phi phenomenon and apparent motion, to somewhat slower (but still fast and involuntary) ones like object recognition, speech recognition, and the like.

The top-down processes, which I called appropriation, are concept-driven, more voluntary, more deliberative, and more extensively funded by experience. A prototypical case would be judging a movie good or bad, or picking a clip to show in class. Interpretation, which I considered in this entry, is a common act of appropriation in the film-viewing community.

In the middle zone are what I called activities of comprehension. A prototypical example is following a story. It’s data-dependent (I can’t make Jackie Chan into James Bond) but it’s also concept-dependent (I can identify the conflicts and combats in a martial-arts film because they make the plot advance in a conventional manner). In non-narrative filmmaking, other comprehension skills come into play, drawing on knowledge bases, heuristics, and the like. You need some experience of art and life to follow the poetic fishing documentary Leviathan.

I wanted to allow feedback too, so the dotted lines in the middle try to suggest how comprehension can fund certain aspects of perception. We recognize Jackie Chan as likely to be the hero, and this concept helps steer our attention to him in his shots. Comprehension of course also funds appropriation, as when after grasping the film’s story we pick it apart in analysis.

One implication, already touched on in the interpretation entry, is this: As we go up from perception to appropriation, the filmmaker’s control wanes and the viewer’s control increases. Spielberg structures Raiders of the Lost Ark the way he wants, but you can appropriate his movie as a piece of imperialist ideology and he can’t do a damn thing about it. In the middle, it’s a negotiation: He steers you to construct the story a certain way, but you can also fill it out with your own inferences, or claim he hasn’t given you enough cues to do so. (Does Marion really love Indy? How much?)

And emotion is involved at all stages of the process, from the jolt of jump scares to the high-level social satisfactions of fandom.

Functions and inferences

Think of all the vending machines you’ve encountered in your life. Each one yielded you those tasty snack treats in a predictable way, but there are different designs and materials. There are those drop-down machines that usually clamp your wrists when you try to reach into their pilfer-proof trenches. There are the little-window ones, which rotate the goodies into place (sometimes). There are even ones that use claws or turntables. And the bits and pieces can be made of plastic or metal, while the gearing and electronics and the machinery for grabbing your money (and denying your change) can be widely varied. But all in all, they have the same basic function and purpose: to take your payment and give you something deliciously unwholesome.

In the same way, my model of the spectator is agnostic about how the processes are instantiated in physical stuff. Doubtless retinas and neurons and inner ears and the nervous system are involved, but I’m not providing the details. I have no idea how to do so. Maybe we should think of the mind as having a core-periphery topography with outward-facing systems (the senses) as discrete modules picking up data while “central systems” supply the top-down treatment. Or maybe the mind is just a tangle of wetware, wires running all over the place, with “higher” functions jammed against, or crisscrossing “lower” ones.

I leave sorting all that out to the experts. But in terms of functions, I think it’s fair to say that most psychologists let the bottom-up/top-down metaphor capture distinct sorts of activities, however they are manifested in our senses, brains, and nervous systems.

More controversial is my argument that these activities are inferential in nature. This signals my commitment to New Look thinking, the early cognitive trend launched by Jerome Bruner, R. L. Gregory, Noam Chomsky et al. Computational models of mind emerged from this research. Nobody doubts that in the comprehension and appropriation phases, inferences are involved. Understanding a story or interpreting a movie as sexist clearly relies on inferences, “going beyond the information given.” The tougher controversy comes with perception.

Following Helmholtz, who believed that perception was “unconscious inference,” the information-processing perspective holds that perception is inference-like. It is defeasible. My eyes can fool me, as with mirages and the bent-looking stick in the pond. This is one reason New Look psychology is interested in illusions.

Moreover, perception operates with assumptions, just as inferences do. Many perceptual assumptions may not be learned but rather “innately specified” to some degree–that is, as presets. It seems, for instance, that we are evolutionarily “wired” to expect light to come from above. It’s also very advantageous for us to be able to separate figure from ground and tell living things from nonliving ones. These basic perceptual acts are funded not only by experience but by presets that steer us in a certain direction. No blank slate here; lots of veins and grooves. And given that we enter a structured ecosystem at birth, rich and flexible innate dispositions can be tuned to information pickup during a critical period. Babies learn fast because they’re primed to set the switches.

This perspective is usually contrasted with the view that holds that perception is “direct.” Most famously, J. J Gibson held that “the information is in the light.” Thanks to evolution and our mobility as creatures, we don’t need any elaborate inferential activity. The input is so redundant that we reliably detect the features of the environment automatically.

I think that the Embodied Cognition theorists are somewhat akin to Gibson in their belief in minimally mediated sensory pickup. Admittedly, though, as Gregory Hickok suggests in The Myth of Mirror Neurons, the Embodied Cognitivists do seem to have a computational side in treating mirror neurons as supplying “representations.” And one strain of Embodied Cognition, identified with George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, denies the inferential and computational model but still adheres to conceptual schemes (like metaphors) as representations of bodily experience. So some categorical, mediating inferences seem to play a role.

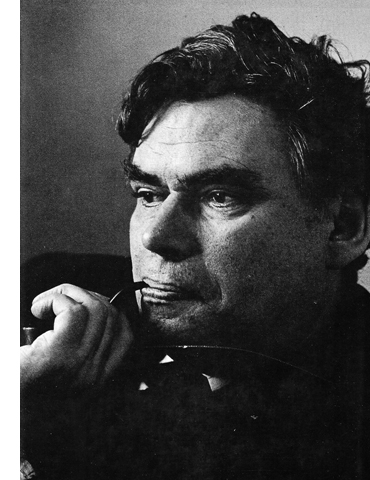

The next section discusses how New Look thinking can help us understand visual arts. My comments target two essays in the 1973 collection Illusion and Nature and Art: R. L. Gregeory’s “The Confounded Eye” and E. H. Gombrich’s “Illusion and Art.”

Gregory, Gombrich, and art

The Penrose steps.

New Look psychologist Sir Richard Gregory (lower right) was a passionate connoisseur of illusions like the Penrose stairsteps. He was famous for pushing the cognitive model of inference-making very far, deep into the basics of perception. He saw perceptions as the usually reliable results of assumptions and hypotheses, in a process significantly similar to what scientists do when they launch hypotheses and check for confirmation. For a career overview, go here.

I take it that he’s trying to answer the question: What perceptual processes generate visual illusions? We evolved to pick up accurate information from the environment, and normally our perception is accurate. The obvious problem with illusions is that they yield false information. What has fooled our eye?

As for perceptual strategies, perhaps in film we could cite special effects and green-screen backgrounds, where perspective, lighting, focus and so on are calculated to suggest space that isn’t really in front of the camera. Our visual system assumes regularities of space that aren’t justified; we usually can’t force ourselves to see these backgrounds as flat.

Some controversies dog Gregory’s theory, chiefly in his reliance on prior experience. He thinks that even pretty low-level outputs depend on knowledge of some sort, if only about our world of discrete edges and solid shapes. He doesn’t seem to treat evolution as shaping many of our perceptual proclivities. In this essay “The Confounded Eye,” he appeals to classical conditioning (p. 66) to get the system off the ground.

But crucial are the ideas we also find in the work of E. H. Gombrich. Gregory assumes an active perceiver, one who takes fragmentary stimuli as cues for building up a perceptual conclusion, through a process of hypothesis-testing. Expectation, assumptions, and probabilities all play a role. Perception is inferential because it can be wrong.

In addition, Gregory reminds us of the importance of habituation (sometimes confusingly called “adaptation”). This means simply resetting the threshold of your sensory input. At first the coffee shop seems noisy, but soon enough you’re paying no attention to it and completely sensitive to your partner’s whisper. People can even adjust to wearing eyeglasses that turn the world upside down! Habituation is perhaps the most robust finding in all of psychology—and something that, when it becomes all-powerful, Victor Shklovsky deplores. (“Habitualization devours works, clothes, furniture, one’s wife, and the fear of war.”)

Gregory’s last book, the cleverly titled Seeing through Illusions (2009), published a year before his death, is a detailed expansion of these ideas. He classifies dozens of illusions according to a richer scheme than the one laid out in his 1973 article.

There’s a lot more in Gregory’s essay, not least the homunculus argument which has been broached against a lot of cognitive theorizing (mine included). But now let’s look at Gombrich’s essay “Illusion and Art.” He was a friend of Gregory’s and he borrowed heavily from New Look psychology.

Despite the book’s title, Gombrich’s magnum opus Art and Illusion doesn’t center on illusion as such. In trying to answer the question Why does [European representational] art have a history? he had to confront “illusionistic” styles, but that issue was secondary to the larger issue of continuity and change in representational traditions. So with an essay called “Illusion and Art,” Gombrich offers a more explicit and careful account of illusion.

I take it that his guiding research question is something like How may we explain the artistic and psychological processes that generate illusion in the visual arts? Not surprisingly, he will make use of some of Gregory’s ideas.

What seem to me crucial here are Gombrich’s reflections on animal perception. Far more than in A & I, he posits a continuum of sensory appeals and so a sort of spectrum of degrees of illusion. To a considerable degree, he has turned my vertical diagram into a horizontal one.

There are automatic, involuntary processes he calls “sensory triggers.” Moving along the spectrum, there are more elaborate strategies for conjuring up illusion, but these will rely on more deliberative processes. Throughout, we never lose the sense that we are watching a representation, however realistic it looks.

Moreover, Gombrich attributes the fast and mandatory illusions, the ones Plato called “lower reaches of the soul,” to evolution. He posits that just like other creatures, we have sensory systems that respond to “triggers” automatically, and sometimes we can be deceived–as predators are fooled by the camouflage of their prey.

So what about illusions? At one end is pure delusion, as with say counterfeit money. Trompe l’oeil is a little further along; you really have to get close to detect the difference. Flat objects, like letters tacked to a board, are good for this trickery, as are fictitious postage stamps like those of Donald Evans.

These cues are very realistic, but crucially the trigger need not be a close replica of what it represents. Approximation can work. The duckling can follow a moving brown box if it moseys like its mother; the box doesn’t look like Mom, it just triggers the Mom-response. Stickleback fish will strike a red cloth that doesn’t look much like another fish’s belly–except in being a moving patch of red. Recall as well the Frog Multiplex. These critters are slaves to innate “action programs.”

A flat, impoverished display of a wiggling worm is enough to get the right (wrong) reaction. And note a fascinating Gombrich example, Houdon’s bust of Voltaire, where the sparkle in the eye is actually a tiny lump protruding from the surface. You couldn’t get farther from a non-realistic device for depicting a gleam of light.

Hence a typical Gombrich formulation: What matters most is stimulation, not simulation. Images at whatever degree of realism rely on key features that trigger our automatic systems. The big transaction isn’t resemblance. The link is not between image and object but between the activities involved in processing the image and those processing the object. The image has hitched a free ride on perceptual habits, or faults, that we already have and cannot always see beyond.

Further along the spectrum, our response can be more flexible, less data-driven. We can learn to control and use the illusion, appreciating it. We can consciously factor in context, prior experience, interpretative possibilities. We can shift mental sets and adjust our expectations, we can test projections by trial and error. We’re now in my realms of comprehension and appropriation–comparatively self-conscious film experiences. But we couldn’t go so far and wide without anchoring our response in the fast, mandatory “lower reaches of the soul,” whose powers derive from evolution.

Gombrich’s essay also emphasizes time more than Art and Illusion had. The sequential nature of perceptual activity–scanning an image–doesn’t occupy him much, but I think it’s quite important. I’ll give an example later on. But he’s right to stress the pressure of time in an evolutionary context. Fight-or-flight decisions have to be made fast, and so creatures with oversensitive mechanisms had a better chance of surviving, even if they sometimes wasted effort in avoiding harmless things. This time dimension takes Gombrich to movies, of course, as well as to flight simulators.

The last main point I’d stress is Gombrich’s insistence that we’re always after meaning. In Art and Illusion he proposes that we never see space as such, but rather medium-size objects in an environment. Representing “space” is tough, but people can provide convincing information about the spatial layout of people, places, and things. Mapmakers do it, technical illustrators do it, we make stabs at it, and painters do it with precision, delicacy, and force. Ditto textures, lighting, and other features of the world.

The “effort after meaning” flows from the inferential, seeking nature of perception. In a memorable formulation Gombrich says we don’t see people’s eyes as such: “We see them looking.” We are geared to meaningful objects, actions, and implications, not purely physical metrics. Again, this makes evolutionary sense. Creatures who focus on measuring the distance between a tiger’s eyes aren’t going to leave as many offspring as creatures sensitive to gaze direction and threatening sounds.

Perceptual psychologists will debate whether the New Look/inferential model or the Direct Perception model of Gibson et al. is better for explaining real-life perception. But as my concerns are in studying art, particularly cinema, I think the inferential perspective is better suited to analyze what concerns me. For one thing, it grants that grasping art is active and skilled, something that I think we all acknowledge. Your and my skills of noticing, understanding, and responding complement the skills of the ‘poet’ or maker. We complete the artwork.

Moreover, artworks offer simplified, streamlined displays very different from the blooming, buzzing confusion of the world. Gibson’s perceiver has to hack through a lot of distractions to extract the texture gradients and optical flow that will specify the layout. Art works already do that for us. Art works, films included, are designed with precision to trip our inferential engines at all levels. As a result, an inferential model tracks more closely the critical analysis we want to conduct on films. I’ll try to give two examples at the end.

A personal detour: Monkey see, David do

The Chinese Feast (Tsui Hark, 1995).

In the 1980s, as I was studying narrative and style in Hollywood films, I was struck by the ways in which the films’ designs seemed to aim for particular responses from spectators. I wondered whether the norms in place were coaxing us to perform particular mental acts: assuming, trusting, hypothesizing, anticipating, and so on. A lot of what we see and hear in a film sets up “intrinsic norms” that in effect teach us how to comprehend the story.

This led me to float an approach to spectatorship based on then-current premises of cognitive psychology. I tried to work it out in Narration in the Fiction Film (1985) and later work. Other researchers found this intriguing (to use a Kristin word) and developed well beyond it. Over the years an entire subfield emerged, with its own journal, conferences, and academic network.

The psychological findings I found most useful for my research questions were rather robust, well-confirmed ones involving informal reasoning: the use of schemas, heuristics (quick and dirty inferential routines), prototypes, and other concepts. I call these findings robust because they’re fairly well-replicated phenomena that different theoretical paradigms have tried to explain. They’re especially useful tools for us as students of the arts, for they bear directly on matters of narrative–plot, characterization, causal connections, and the like. They map fairly comfortably onto our analytical categories.

The broad point is that just as visual illusions exploit deficits in our visual system, narrative often plays to biases and shortcuts in more elaborated inferences. We’re good at tracking cause and effect, but the principles we use are “folk psychology,” not the principles of physics. In real life, we may attribute Oscar’s grumpiness to his just having a bad day, but Oscar is a film character and is introduced to us grumpy, we’re inclined to take him as a permanent grouch. (This is called the fundamental attribution error.) This example also trades on the primacy effect, also known as anchoring, which lets the first instance we encounter shape our pickup of information encountered later.

A prime instance of a robust finding was research into eye-tracking.

Film theorists have long considered that attention is central to filmic effects. Once eye-tracking devices became easy to use, researchers could use them to study how people scanned movie images. The pioneering work here was done by Tim Smith. I survey the research program here, and Tim did a powerful guest blog to follow up. His entry, probably the most popular post we ever had, earned him press coverage and a guest visit to film companies to present his research!

For more discussion of these middle-level findings, you can see this reader-friendly version.

Many of these activities are accessible to us, if only in retrospect. In following a narrative, if we pause the movie, we can think about what we’ve noticed and what we expect. As the years went by, though, I began to realize that probably a lot of what engaged us in films wasn’t so easy to tap consciously. Plato’s “lower reaches of the soul” invoked by Gombrich played an important role.

So in the 2000s, when research into mirror neurons was emerging, I drew two lessons. One was that certain primates could respond to film images much as we do–recognize objects, track movements, and so on. I thought, and still think, that this is an exciting piece of information. What was methodology for the researchers is a substantive finding for us. If macaques can recognize what a movie shows, it’s hard to argue that pickup depends on cultural codes.

Second, I thought that the prospect of mirror neurons held promise for carrying inference/computation down into the wiring level. Given all the presets supplied by evolution, isn’t it conceivable that social primates may have evolved to “resonate” to actions, expressions, and even emotions displayed by their conspecifics? It would be another part of a natural endowment that, suitably tuned by the social environment during the critical period of growth, could bootstrap a broader set of skills–such as following stories.

Hence the remarks I made in my 2008 “Poetics of Cinema” essay, where I took the view that “it seems we have a powerful, dedicated system moving swiftly from the perception of action to empathic mind-reading.”

Fairly soon mirror neurons became absorbed into a larger trend toward neuroscientific examination of film viewing. I’m not sufficiently expert to appraise that work, but I do have thoughts about what it can, and can’t, tell us about understanding film.

Mirror, mirror in your head

As I understand it, the Embodied Cognition research program aims to answer this sort of question: What role do automatic, low-level visual processes play in enabling spectators to respond to film? More specifically, do the processes enable us to understand and empathize with action, agents’ intentions, and agents’ emotional states? I think that the general answer proposed is yes.

Mirror neurons play a role in this process. They were first discovered in macaque monkeys, and there is some evidence that they exist in humans. The hypothesis is that when we see a piece of action, in life or in cinema, we spontaneously mimic, in the pattern of cell firings in our brain tissue, the sensory and motor processes that create it. Our brain mimics or “resonates with” the action we perceive. We don’t just “understand” that the man is lifting a glass; in a weakened form we are repeating the experience of his doing so. Of course we may not be holding a glass, but to a degree the sensory and motor cells in our brain tissue rehearse the lifting gesture. Because we’ve executed similar actions, the cell firings are marked out through electrochemical patterns.

This argument takes us into the specialized areas of brain science. A useful account of the general scientific debate is here. The appended articles quickly turn technical, though. An easier read is this piece in Wired. For film, the fullest account of this view is provided by Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra in their recent book, The Empathic Screen: Cinema and Neuroscience.

In our next blog entry, a guest post, Malcolm Turvey will offer an analysis and critique of that book’s arguments. As a pendant to that, I’m just going to signal my reservations about the project and its results. In the last section of this entry I also want to make a point that Malcolm will explore conceptually: How much specificity does a “psychology of cinema” need for us to say useful and unusual things about film?

My first general comment: What the authors mean by understanding, or “involvement,” or the “from the inside” part of experience could do with more specifying. Malcolm will explore this question in detail. In addition, I wonder whether concepts like “identification” and “immersion” fruitfully characterize our engagement with all films, or even those we find exciting.

Camera movement occupies a privileged place in Gallese and Guerra’s scheme. “The involvement of the average spectator is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements.” Yet what about the first thirty years of cinema, in which camera movement is quite rare? Tableau cinema, as discussed in many entries hereabouts, was presumably quite effective in moving audiences. If camera movement automatically steps up engagement, why didn’t it become more common sooner? And are we talking only about camera movements forward, which are the privileged examples cited from Notorious, The Spiral Staircase, and other 1940s films?

The only effects of the nonmoving camera noted by Gallese and Guerra are expressive ones. “In the absence of movement the editing and arrangement of figures and spaces within a shot can produce a feeling of oppression.” Well, editing and staging within a fixed shot can indeed produce that effect, as we see in Antonioni, but it need not. This makes especially curious the authors’ claim that Dreyer’s La Passion of Jeanne d’Arc, with its close-ups, is a static film evoking through editing “the violent shades of power and persecution.” But of course from start to finish Jeanne d’Arc contains many camera movements.

And are we to assume a “progressivist” conception of history, so that the Steadicam is a step toward “better” (=more engaging) filmmaking? Would all those spectators aroused by crosscut last-minute rescues, from Griffith to Black Panther, have been even more carried away if there had been more camera movements?

Gallese and Guerra don’t assert that every shot would be improved, immersion-wise, by adding camera movement. We also need, they claim, more calm and stable orienting shots so that camera movements can create “peak moments” for maximum impact. Yet, to revert to their favorite director, Hitchcock created quite a peak moment in a certain shower scene wholly through editing. Again, would a flurry of camera movements have made it even more visceral? In fact, the leave-taking camera movement that ends this scene serves as the calm after the perceptual onslaught of cuts.

Of course Gallese and Guerra realize that camera movements aren’t the be-all and end-all of cinematic technique. Yet their discussion of editing seems to me rather unrevealing. Their experiment in varying camera angle through cutting yields the conclusions that “we use the same processes that we employ in our visual perception of the real world” and that our brains register violations of continuity rules to some degree. I am not surprised, though it’s good to have confirmation.

Malcolm will take up several other areas of inquiry in his followup entry. I want to end with a couple of examples to set us thinking about the difference between the neuroscientific arguments and those from a poetics perspective. Here’s a chance to weigh research questions against one another, to see the sort of ideas and information each can yield.

Direction and misdirection: Delicacy via precision

Let’s ask a poetics-weighted question: How can viewers understand the construction of shots designed for perceptual force and narrative comprehension? At the least, we should expect that the pictorial design will solicit attention and emphasis. Deploying these ideas enables us to talk about deflected attention and gradation of emphasis. And we need not assume that the camera is a surrogate for us.

In Summer at Grandpa’s, Hou Hsiao-hsien gives us a somewhat episodic tale of kids sent to live with their grandparents while their mother is hospitalized. In the village they play with the local children and have minor brushups with their stiff grandfather. They’re exposed to aspects of life and death that the modern city has shielded them from. One of those is a madwoman who wanders through the countryside keening.

The boys won’t play with the little girl Ting Ting. So, bearing the toy fan she always carries, she wanders to the railroad tracks and stumbles in the path of a train.

The madwoman’s rescue of Ting Ting is a harrowing, gripping moment. (No need to be energized by camera movement.) The pounding rush of the train, very loud, is an assault on us. The narrowness of her escape is emphasized by glimpses of the two huddling on the other side of the tracks. No need for camera movement to amp up this jolting moment.

But Hou has introduced something else, the fallen fan that tips over and just barely escapes being crushed by the train wheels. Its childishness–pink and orange and green, tipped over by the rush of the wheels–is a kind of stand-in for Ting Ting. It also, by virtue of color and the absence of anything else to look at, rivets our attention.

No less striking is this: When the train has passed, the fan’s blades reverse direction and spin the other way! This tiny bit of movement, visible on a big screen if not here in miniature, provides a kind of coda for the shocking action. This exemplifies, for me, Gombrich’s “visual discovery through art.” We see wind power in miniature, in a natural experiment in the sheer physics of a situation.

All of which proceeds from careful craft decisions. Hou has stretched the norms of framing and staging in fresh ways to achieve a powerful effect. Nothing I see in the mirror-neurons story could address, much less functionally explain, what’s on display here.

Similarly, the Embodied Cognitivist position seems to me too coarse-grained to capture the rather different range of artistic effects in a sequence from River of No Return. Matt Calder and his son Mark help rescue Kay and Harry from their clumsy efforts to raft their way to town. Preminger films the rescue in shots that exploit the CinemaScope ratio. Many critics have noticed how Kay’s wicker trunk of clothes falls into the current and remains visible far into the distance as the dialogue in the foreground develops.

Since the arc of Kay’s character traces the gradual stripping away of her past life as a dance-hall entertainer, this phase of her change is made visible in a soft-pedaled way. Attention and emphasis are played down. Preminger prepares us to watch for secondary and tertiary areas of importance–what Charles Barr has called gradations of emphasis. Alert viewers may notice the drifting basket, others not, but for those who do some inferences will be forthcoming. For one thing, What might be the significance of this basket?

Turns out that this was practice for using our eyes. Having prepped us at the riverside, Preminger again plays with graded emphasis. Before the rescue scene, Matt and Mark share coffee before going out for target practice.

Few of us will notice the rifle in its long holster there on the back wall until Matt takes it down.

Now compare this later scene.

Sparse as it looks, the main shot is busy. The men were decoys but the holster was waiting there to be used at just the right moment. We could have noticed it at any time. Maybe some folks did.

When the rifle pokes into the shot, stressed by Harry’s line, it probably surprises us. But those of us who may have noticed the empty holster earlier may experience suspense rather than surprise: Where did the gun go? We have to wait and see.

This sort of multilayered visual effect seems to lie beyond the sort of responses that G & G attribute to aggressive camera movements. We may not be “immersed,” but we are definitely engaged–albeit coolly. The image is a visual display we search, not a space we imagine ourselves interacting with.

You may say that this sequence is so atypical it’s unfair to use it as a counterexample. But I think it’s just an extreme instance of what filmmakers are doing all the time. Preminger uses classic cues: the holster is isolated, it’s sitting near the center of the picture format, and it’s well-lit. On the big screen in a 1954 movie house, it would be very evident, in principle. And we’ve seen it used before in a very similar camera setup.

But Preminger has steered us away from what’s important by creating competing centers of attention. There are the men’s faces and gestures, the words spoken the dynamically unfolding drama, the woman and the boy executing repetitive actions (what Gombrich in Art and Illusion calls the “etc.,” take-as-read principle). Attention and emphasis are led by lines of least resistance; you’d have to be pretty stubborn to study that holster.