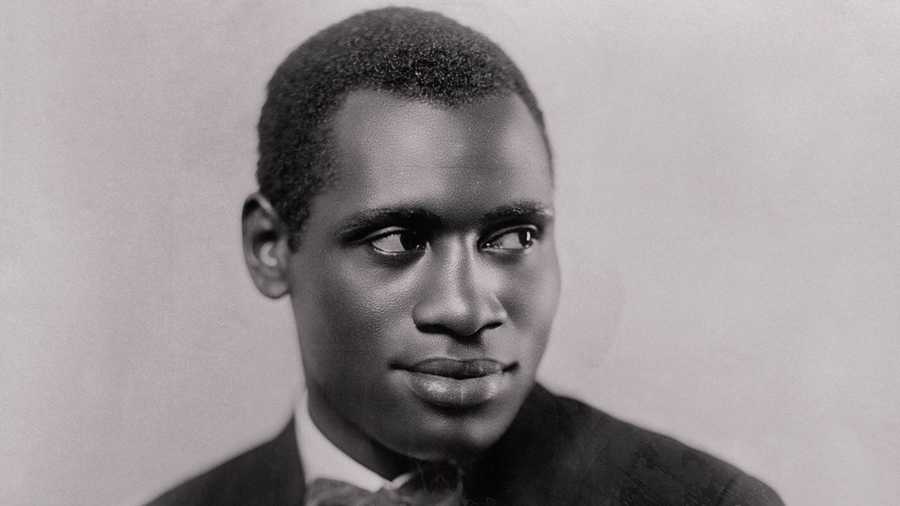

“It is an altogether extraordinary life, the stuff of epic,” writes Simon Callow, having just taken us from milestone to milestone in the first fifteen paragraphs of an outstanding piece for the New York Review of Books. “And now, it is hard to find anyone under fifty who has the slightest idea who he is, or what he was, which is astonishing—as a singer, of course, and, especially in Proud Valley, as an actor, his work is of the highest order. But his significance as an emblematic figure is even greater, crucial to an understanding of the American twentieth century.” The life, of course, is Paul Robeson’s, and the occasion is the publication of “two new books about him, as different from each other as chalk from cheese. Gerald Horne’s Robeson: The Artist as Revolutionary is baffling,” while Jeff Sparrow’s No Way But This: In Search of Paul Robeson “is the polar opposite of Horne’s book, a work not of assertion but of investigation. . . . The result is arresting, illuminating, and ultimately upsetting.”

Jonathan Rosenbaum’s recently posted his afterwords to published editions of screenplays by Orson Welles, The Big Brass Ring (written with Oja Kodar in 1981 and 1982) and The Cradle Will Rock (1984). Rosenbaum suggests that “The Cradle Will Rock might be said to bear some of the same relationship to its predecessor as The Magnificent Ambersons has to Citizen Kane: after a flamboyant and fearless speculation about corruption, a modest and highly self-critical reflection on the brashness of innocence, tinged with sweetness and nostalgia.”

“There are a handful of silent films that most cinephiles see first,” writes Pamela Hutchinson. “Battleship Potemkin, Metropolis, Sunrise, The General, and The Cabinet of Dr Caligari perhaps, give or take Nosferatu, a Hitchcock and a couple more Hollywood favorites. There is nothing dismaying about the establishment of these films as classics of the silent era,” but Lawrence Napper’s Silent Cinema: Before the Pictures Got Small “offers a broader picture of film style and the film industry between the First World War and the coming of sound.”

Adrian Martin’s collection Mysteries of Cinema: Reflections on Film Theory, History and Culture 1982-2016 will be out on May 28.

A few days ago, Girish Shambu alerted us to the new site collecting work by scholar and critic Erika Balsom, and there we find links to the introduction to her latest book, After Uniqueness: A History of Film and Video Art in Circulation, to the introduction to the 2016 collection co-edited with Hila Peleg, Documentary Across Disciplines, and to the entirety of her 2013 book, Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art.

Karina Longworth has launched the You Must Remember This Book Club, which is less of a club per se and more of a reference guide. Click on any one of the dozens of covers on that page and up will pop a link to the episode of the YMRT podcast which that book informed.

Leonard Maltin’s recently written up a list of newish books that includes his notes on Vanda Krefft’s The Man Who Made the Movies: The Meteoric Rise and Tragic Fall of William Fox, Nancy Schoenberger’s Wayne and Ford: The Films, the Friendship, and the Forging of an American Hero, and ten more.

“Cult Epics Comprehensive Guide to Cult Cinema, edited by Nico B, is a large format hardcover silver-edged full color compilation detailing a thorough history of the niche he's carved,” writes Jim Tudor at ScreenAnarchy. “A limited edition of 1000 copies, the book is divided into sections and subsections with individual essays on certain topics, films and filmmakers. Spotlighted directors include the recently departed Radley Metzger, Walerian Borowcyzk, Gerald Kargl, Agusti Villaronga, and the vintage Bettie Page-starring work of Irving Klaw, among many others.”

“I’ve only just discovered Camera Over Hollywood: Photographs by John Swope 1936-1938, and a discovery it is,” writes José Arroyo. “John Swope was a life-long friend of Henry Fonda, James Stewart, and Josh Logan. They all met in their early twenties when they were part of the University Players theater troupe in West Falmouth, Cape Code, Massachusetts; and they all found success: Josh Logan as a legendary writer and director in post-war Broadway (and a rather mediocre film director); Swope as a photographer and regular contributor to LIFE magazine; Fonda and Stewart need no introduction.”

Writing for Film International, Tony Williams finds James D. Stone’s America Through a British Lens: Cinematic Portrayals 1930–2010 to be “a readable, stimulating, and well researched study.”

Peter Nellhaus reviews Melanie Williams’s Female Stars of British Cinema: The Woman in Question, noting that “a certain amount of anglophilia in addition to cinephlia may be required.”

For news and items of interest throughout the day, every day, follow @CriterionDaily.

from The Criterion Current http://ift.tt/2DOrs0n

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento